When news broke that U.S. track star Sha’Carri Richardson would be banned from the 2021 Olympics after testing positive for Cannabis, Al Harrington just shook his head.

“I thought it was bullshit,” the retired NBA veteran said of Richardson, who admitted to medicating to cope with the recent death of her mother.

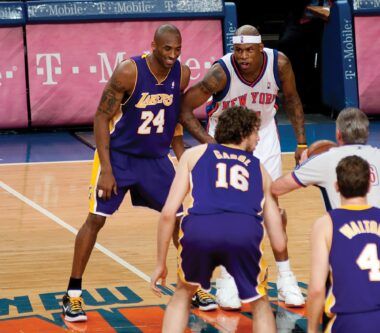

Never one to mince words, the 41-year-old overcame enough adversity during his 16-year career, which included stops in seven different cities to learn there are a variety of ways to combat pain – and not all are good.

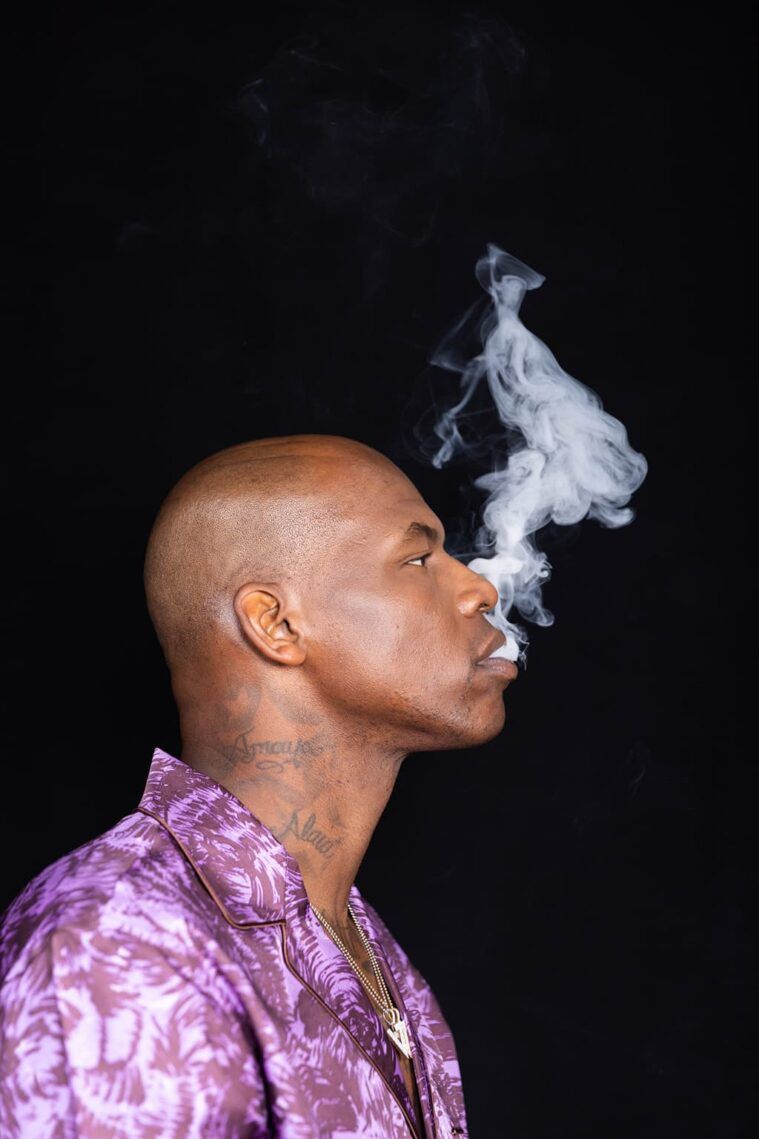

By the end of his athletic journey, Harrington found himself hooked on a thrice-daily dose of painkillers to battle chronic inflammation stemming from a variety of operations on his back and knee.

“In Denver, I had a botched knee surgery – the team doctors sort of screwed me,” he said. “I had a PICC line in my arm and I was on all these medications. I felt horrible. My business partner Chloe came to see me and suggested I try CBD. I put some on and my legs started feeling better, my elbow started feeling better.”

Harrington has been out of the league since 2014 and hasn’t taken a pharmaceutical drug since. During that time, he has used his star power to become a leading voice in the fight for medical Cannabis, creating The Harrington Group – an organization that includes a trio of Cannabis enterprises that operate in six states (Colorado, Oregon, Michigan, California, Arizona, and Nevada).

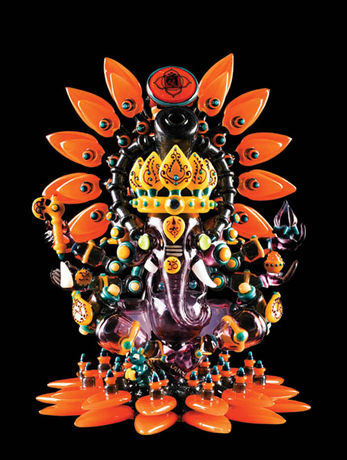

Viola Brands was the first of his creations, originating in 2011. The brainchild of his grandmother, Viola – a sweet, church-loving lady who struggled with chronic pain stemming from glaucoma and diabetes. Al convinced a then 79-year-old Viola to use CBD, improving the quality of her golden years.

“For someone like my grandmother to try it and have it work – for how religious she was, and growing up in the 1930s when prohibition started – it really spoke volumes to me,” the New Jersey native said.

Breaking the social stigma that surrounds medical Cannabis is difficult, especially within an African American household, Harrington said. The 6-foot-9, 245-pound power forward grew up during the height of the “Just Say No” era, where stop-and-frisk policies regularly placed young Black and brown men in jail for possession of marijuana. Becoming a daily consumer was hard enough, nevermind a business mogul.

“People from the Black community really have a form of PTSD with how [Cannabis] has affected their community,” he said, noting a high number of arrests in the city of Orange where he was raised. “Growing up, it was drilled into our heads that it was a gateway drug. My grandma used to kick my aunts and uncles out of the house for smoking, and my mom used to get into it with my stepfather about it, too. I was scared that I’d get into something bigger.”

Two seasons in Denver changed Harrington’s perspective, including his final year when public support allowed Colorado to become the first state in the nation to legalize recreational Cannabis in 2012.

“I was seeing people walk out of stores with weed and I was like, ‘Oh shit, you can do this?’” he said. “I don’t know where I’d be right now if I hadn’t been there at that time. I’d probably be coaching basketball somewhere or playing golf.”

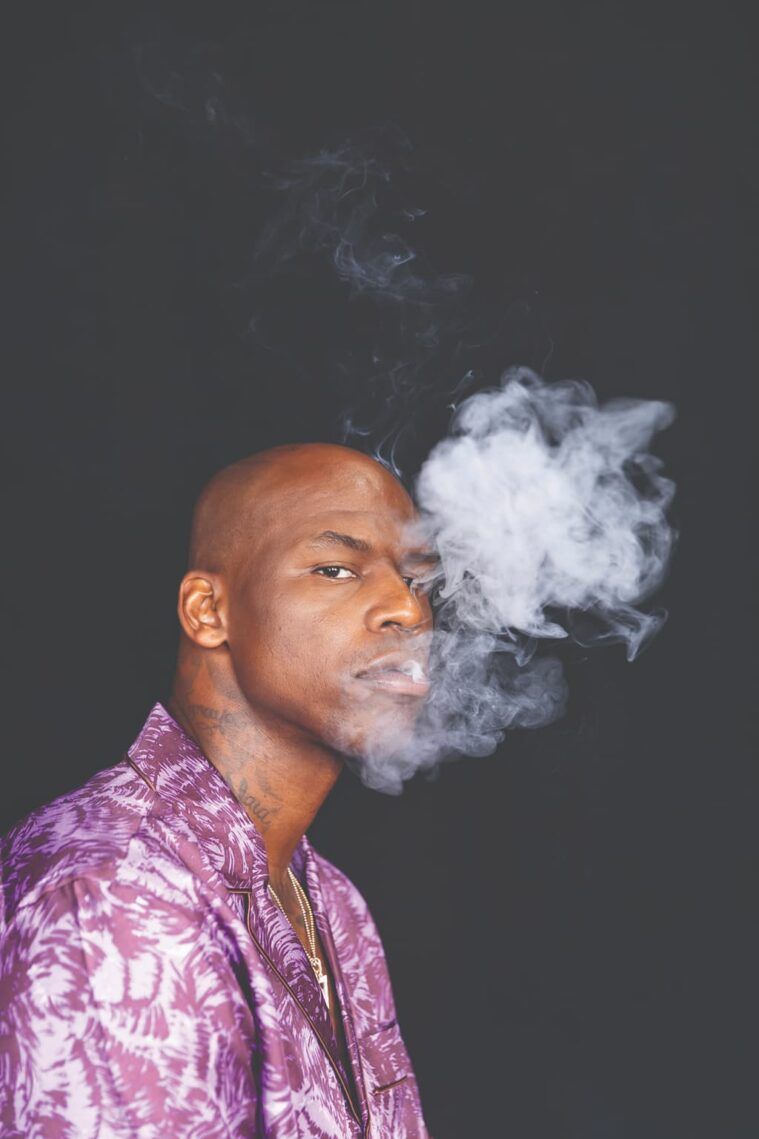

He sees the creation of The Harrington Group as an opportunity to create generational wealth and open up opportunities inside communities of color. Last year, the company rolled out Viola Cares, a philanthropic initiative which aims to help formerly incarcerated people transition back into society. Harrington made waves by claiming it was the mission of Viola Brands to turn 100 Black individuals into millionaires over the next few years.

“Now I can’t just give a million dollars out to people,” he smiled, admitting the line may have been taken too literally. “It’s about finding people with ambitions and the visions of an entrepreneur. Then we can tap into resources and fund their opportunities. We’re a high-quality brand, but we also want to use that recognition to bring people of color into this industry and make them successful. We want to be able to inspire economic empowerment and lift each other up.”

Sports, he says, will continue to be a vessel that drives his entrepreneurship, as well as advocacy on behalf of new and current patients. Harrington remains in close contact with the National Basketball Players Association in hopes of educating players on the benefits of CBD, as well as the pitfalls of painkillers.

“For me, that’s the easiest to use,” the 1998 first-round draft pick said. “One thing we don’t realize is that the same way we all eat food, the same way we all listen to music – people from all walks of life use Cannabis.”

Even world-class athletes like Sha’Carri Richardson.

“The [International Olympic Committee] is going to have to reevaluate the way they do things,” he said. “In the U.S., we lead everything. Here, you see the way professional leagues have taken it off the list, or turned their back on testing for it. It’s become a very common thing to do.”

“Is anybody thinking it made her faster?” he laughed.

“It’s nonsense, but hopefully it shines a big enough spotlight on this to make a change.”