Setting the Standard

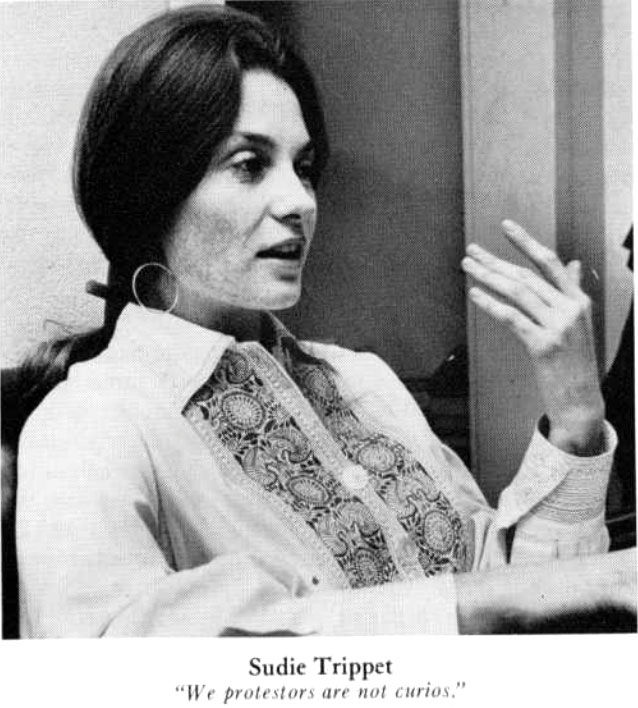

Lifelong civil rights activist Pebbles Trippet is one of the most respected elders in the Cannabis community, and with good reason: it’s her courageous legal battle nearly 30 years ago that established a patient’s right to legally transport their medicine and to possess as much Cannabis as deemed necessary by their doctor — a precedent-setting policy known as the Trippet Standard.

A Born Activist

Mary Susan “Sudi” Trippet was born Nov 10, 1942, in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. As early as the age of five, she began suffering from excruciating migraines.

“I just remember pounding my head against the backboard of the bed in order to counteract the pain,” she recalled.

Between headaches, her youth was dominated by two passions: athletics and activism. At the age of 13, she became aware of Rosa Parks, the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Emmett Till’s lynching, and they deeply affected her.

“This was a part of my generation … it was happening in real time, and I was paying attention.”

The most important lesson she learned from the bus boycott, she said, was how to beat the system.

“I thought, ‘Oh, so that’s what you do to win — you come together for a common purpose, and you stick together.”

The Power of Protest

In college, Trippet devoted herself to activism — joining the Students for a Democratic Society, founding the Committee to End the War in Vietnam and organizing an anti-war rally on campus that drew over 100 people. In 1960, she participated in the NAACP’s lunch counter protests to integrate Tulsa’s eateries. And in April 1965, she helped the SDS organize the first national protest March on Washington against the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, these acts of civil disobedience incited threats of violence against her.

“At some point, a bomb came in my front door, sent by the Minutemen,” she told Fat Nugs Magazine last March. “Luckily, it didn’t go off … but it singed the walls and me a little bit, and I decided to move.”

After college, she moved east — first to New York and then to Boston — where she spent about four years working odd jobs, ramping up her activist efforts. She joined the Socialist Workers Party, but due to ideological disagreements, she and her partner-in-crime, Robert “Stoney” Gebert (aka “Geb”), were expelled from the group.

“They brought me up on charges and kicked us out of the SWP,” she told Fat Nugs. “I had already decided that they were too backwards … the anti-gay policy, and the anti-weed policy, they were no good for me … so I left.”

Amid the growing momentum of the hippie movement in the late 1960s, Trippet did what thousands of other young idealists did — she headed to California.

California & Cannabis

In 1972, Trippet moved to Los Angeles, where her activism shifted toward two new issues: LGBT rights (a subject that, as a bisexual woman, was deeply personal to her) and marijuana legalization. (Since first trying Cannabis during college, Trippet had learned that it could prevent the horrific pain of her migraines and had been using it regularly.)

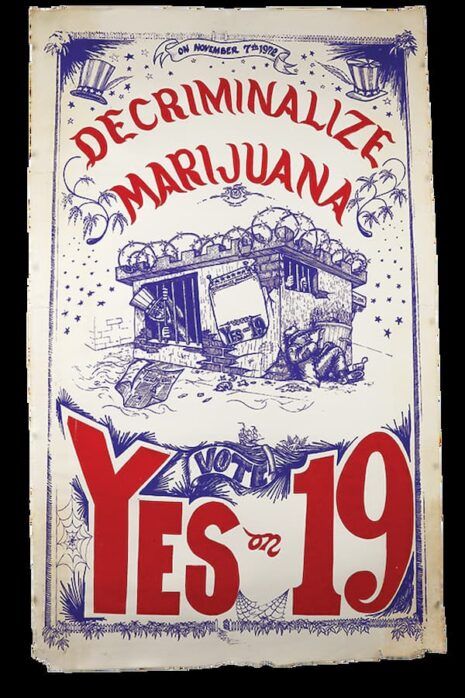

Trippet joined the nascent pro-pot movement in their effort to pass the California Marijuana Initiative (aka Prop 19) — helping to gather the 326,000 signatures needed to get it on the ballot. Despite winning only 33% of the vote, advocates viewed the turnout as a victory. Their second initiative, two years later, also failed, but more localized efforts would soon prove successful: namely, the Moscone Act of 1976, making possession of up to an ounce of marijuana in San Francisco a misdemeanor rather than a felony, and 1978’s Prop W, recommending that the city’s district attorney and cops not enforce federal marijuana laws.

After years of splitting her time between Los Angeles and the Bay, in 1978 Trippet relocated to a commune in Mendocino County, where the members all chose new hippie names. She went through several nicknames that didn’t stick before finally hitting on the right one: As she tells it, when a Chinese girlfriend named her Black Jade because it was the rarest kind, she replied that she preferred the commonest kind, so it became Black Pebble. Then, after dropping the Black and adding an “s,” she became simply “Pebbles.”

“It really does fit me … because I am the commonest kind — I am of and for and by the people.”

Bay Area Bust

In the 1980s, Pebbles and Geb formed the California Marijuana Reform Initiative Coalition, an organization that promoted progressive ballot initiatives. They got significant measures passed, including an Apartheid Consumer Boycott, a “Nuclear Free Zone” in SF and an AIDS Research Initiative.

“I went to bat for any cause that was about human rights, civil rights and ways of making change,” she said.

Unfortunately, that activism made them targets of law enforcement. On May 8, 1982, the SFPD raided CMRIC’s offices as part of an undercover sting operation and found small quantities of weed and around 2,000 doses of LSD. Narcotics agents arrested Trippet, Gebert and four others, charging them with misdemeanor Cannabis possession and felony possession with intent to sell LSD. Trippet cried entrapment and accused the police of harassment, claiming that the operation was planned as a way to short-circuit their latest initiative. Nonetheless, she was convicted and served three years’ hard time.

Despite this setback, she remained closely involved with the burgeoning medical marijuana scene spearheaded by Dennis Peron, “Brownie Mary” Rathbun and Dr. Tod Mikuriya — promoting the Cannabis Buyers’ Clubs, serving on the organizing committee for Proposition 215 and helping to supply Rathbun with Cannabis to make her “benign brownies” for AIDS patients and veterans.

Pleading Her Case

Throughout the 1990s, Trippet was busted ten times in five different counties. The most consequential of these arrests took place on Oct. 17, 1994, in the Berkeley Hills area of Kensington. After being stopped for a traffic violation, police discovered around two pounds of leaf in her vehicle and charged her with felony transportation of a controlled substance.

At trial, she first mounted a religious-use defense, then a medical-necessity defense. Dr. Mikuriya testified on her behalf, saying that Cannabis was indeed effective for her condition, and that if it were legal for him to prescribe to her, he would. Nevertheless, she was found guilty and, on February 20, 1996, sentenced to six months in jail.

But Trippet had expected to lose — the reason she chose to go to trial rather than take a plea deal was to challenge the constitutionality of the law. She filed an appeal, and as fate would have it, her first day back in court was November 4, 1996 — the day before Prop 215 was voted into law. With medical marijuana now legalized, her medicinal defense had new legs. Unfortunately, her attorneys weren’t on board with her strategy, so she fired them and opted to go it alone — visiting UC Berkeley’s law library to educate herself on past Cannabis cases and court procedures.

In addition to her appeal, Trippet also filed an amicus brief with the U.S. Supreme Court challenging the constitutionality of the Controlled Substances Act — arguing that penalties for medical marijuana are “excessive and disproportionate,” constituting “cruel punishment,” and that confiscating said medicine amounted to “unreasonable seizure.” Unfortunately, the court rejected her petition.

The Trippet Standard

Luckily, though, she had better luck with the appeal. Representing herself, she argued that the Compassionate Use Act applied retroactively to her case, and that the right to transport her medicine — though not explicitly stated in the law — was implied by it. She also argued that since she needed to smoke up to five “fatties” a day to keep her headaches at bay, she should not be held to the preset legal limit of 28.5 grams.

Remarkably, on Aug. 15, 1997, the First District Court of Appeals agreed with her, ruling that if a patient has a legal right to possess Cannabis, they also have a right to transport it. They also ruled that the quantity of Cannabis a patient can possess should be “reasonably related to the patient’s current medical needs,” as determined on a case-by-case basis based on the physician’s approval — a new legal guideline dubbed the “Trippet Standard.” Her case was then remanded back to the lower court, where the charges were dismissed.

It would be nearly a decade before that standard was put to the test. In 2003, California passed SB 420 — establishing new regulations for medical Cannabis. In that bill was a section that set a limit of 8 ounces of dried marijuana and six mature or 12 immature plants per patient — a policy in direct conflict with the Trippet Standard. Two years later, the LAPD searched the home of medical marijuana patient Patrick Kelly and found 12 ounces and seven plants, and charged him with exceeding the legal limit. He was convicted, but the conviction was overturned, and when it reached the state Supreme Court in January 2010, they ruled that Prop 215 trumped SB 420, and thus the Trippet Standard was upheld.

Enduring Legacy

Thanks to her historic legal victory, Trippet has been honored with three lifetime achievement awards: from the Emerald Cup in 2003, from Women Grow of Mendocino in 2016 and from the California State Fair Cannabis Awards in 2024 — an award that, like the law she helped establish, has been named after her.

Trippet has spent much of the past 30-odd years living off the grid on her property near Albion, California. While there, she co-founded the Medical Marijuana Patients Union, the Mendocino Medical Marijuana Advisory Board and the Cannabis Elders Council, as well as creating Cannabis Cards – trading cards honoring stoner heroes.

Sadly, though, the long, difficult legal battle has taken a toll on her. Unable to maintain a steady job for many years, she had to sell activist literature and promotional materials on the streets to get by. In 2023, she was forced to start a GoFundMe and sell her cottage in Mendo to survive. She spent around two years living at Emerald Cup founder Tim Blake’s Area 101 compound in Laytonville before moving in with a friend in San Francisco who now takes care of her.

Now 83, Trippet has also been struggling with several debilitating ailments, including severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, which makes it difficult for her to breathe and speak. But despite her failing health, Pebbles’ radical spirit and commitment to the cause remain undimmed.

“A Roe v. Wade-type constitutionality challenge is what matters now,” she insisted. “I’m confident that if some lawyers would just come forward and take it to the Supreme Court on civil rights grounds, we would win.”