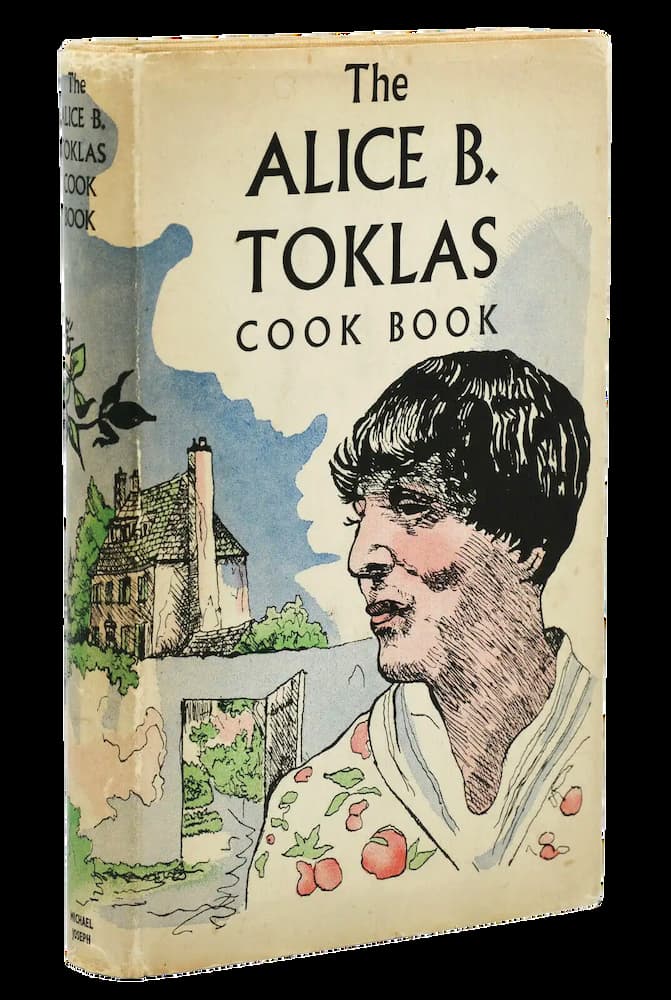

Since “The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook,” released in 1954, contained the first Cannabis recipe ever published in the modern age, many consider its eponymous author an early icon of the marijuana movement. But the true story behind that infamous recipe, and Alice B. Toklas’ reputation as the “Mother of the Pot Brownie,” may surprise you.

From Frisco to France

Originally from San Francisco, Alice Babette Toklas was the daughter of affluent Jewish merchants who’d emigrated from Poland in 1865. The family moved to Seattle in 1890, but moved back to the Bay after her mother died of cancer in 1897. At just 19, Alice became the woman of the house – cooking and cleaning for her father, brother and uncles.

After the great earthquake and fires of 1906, Toklas met Leo and Sally Stein, art collectors who’d emigrated to Europe years earlier. Enraptured by their romantic tales of Parisian life, she and her friend Harriet Levy escaped to France five months later. Within 24 hours of arriving in Paris, Leo introduced Toklas to his sister, modernist writer Gertrude Stein, and it was love at first sight.

The Odd Couple

In the months that followed, Stein and Toklas became inseparable. The two women had much in common: both were well educated, well-traveled, and came from wealthy Jewish families in California. And yet, they seemed an odd mismatch: Stein was as a large, confident, gregarious woman with short gray hair, while Toklas – who sported a brown “Joan of Arc” haircut – was described in one of her book’s introductions as “tiny, birdlike and self-effacing… stunningly ugly, with a huge beak of a nose and an unabashed black mustache.”

Despite their differences, however, their affection was undeniable – so much so that, while on a trip to Normandy in 1908, Stein proposed to Toklas. From then on, they considered themselves married and were remarkably open about their love in a time when homosexual relationships were predominantly kept under wraps.

Bohemian Rhapsody

In September 1910, Toklas moved in with Stein, becoming not only her lover, but also her housekeeper, cook, secretary, editor, and muse – managing her affairs so that she could focus on her writing. Together, they turned their two-story museum-like home at 27 Rue de Fleurus into the Bohemian Era’s most renowned artistic and literary salon – a social hub where the cultural elite (including legendary writers and artists like Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, T.S. Eliot, Henry Miller, James Joyce, Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Paul Cézanne) would gather to drink, dine, converse and collaborate. These symposia were typically catered, but on occasion, Toklas would cook and quickly earned a reputation as a maestro in the kitchen. In fact, legendary gourmet James Beard once said of her: “Alice was one of the really great cooks of all time.”

Fame & Finality

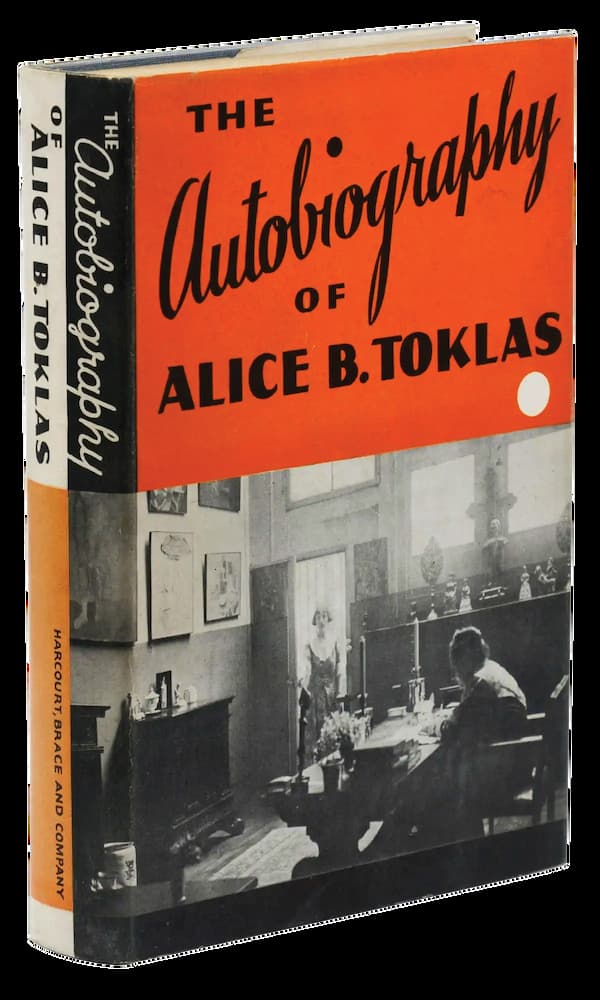

Over the next two decades, Stein’s notoriety continued to grow throughout Paris; Toklas, however, remained relatively unknown. But that would change in 1933 with the publication of “The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas” – a facetiously titled memoir written by Stein, but using Toklas’ voice. It became Stein’s first bestseller, leading to a book tour in America in 1934 and to international fame for both women.

During World War I, the women delivered medical supplies to support the troops. During World War II, they managed to evade the Nazis by hiding in the south of France and selling art to survive. Sadly, though she escaped the horrors of the Holocaust, Stein could not escape the ravages of stomach cancer; on July 27, 1946, Gertrude Stein died during surgery, leaving her common-law wife of nearly 40 years a widow.

It’s a Cookbook!

Because Stein’s “marriage” with Toklas wasn’t legal, her relatives took control of the estate. And though Stein had willed her invaluable art collection to Toklas, she couldn’t sell any of it without the trustees’ approval. As a result, 75-year-old Toklas was left broke and desperate.

In hopes of generating income, she inked a deal with Harper and Brothers in 1952 to write “The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook.” Far from an ordinary cookbook, it would be an eccentric epicurean anthology filled with anecdotes about her adventures with Stein and their famous friends, poetic descriptors, and wry humor. What’s more, most of the recipes were, according to biographer Janet Malcolm, “too elaborate or too strange to attempt.”

As her March 1953 deadline approached, Toklas realized she was falling far short of her 70,000-word obligation and began soliciting submissions from friends. It was one of these 80-plus “Recipes From Friends” that would soon make Toklas’ work the most infamous cookbook in history.

Moroccan Majoun

Brion Gysin was a gay British writer/artist living in Paris who’d met Toklas back in the salon days of the 1930s. In 1950, he reconnected with her, and she encouraged him to go live with composer/author Paul Bowles in Tangier, Morocco – an “international zone” that had become a hotbed of hedonism and free expression for artists and libertines from across the globe.

Shortly after moving there, Gysin hooked up with a painter named Mohamed Hamri. It was Hamri who allegedly introduced Gysin to smoking kif, as well as a decadent delicacy infused with kif called majoun. A pastry ball made from dried fruits, nuts, honey, and spices, majoun is regarded as one of history’s first Cannabis edibles (dating back to the 11th century). In early 1954, Gysin and Hamri opened a café for outlaws and expats called 1001 Nights, in which they reportedly served this Cannabis confection to their counterculture clientele. And so, when Toklas reached out to request a recipe for her cookbook, Gysin – ever the provocateur – decided to have some fun with the old lady.

What the Fudge?!?

Gysin renamed his majoun recipe as “Haschich [sic] Fudge (which anyone could whip up on a rainy day)” and penned a sensational, tongue-in-cheek intro for it:

“This is the food of Paradise – of Baudelaire’s ‘Artificial Paradises’ [a reference to the French poet’s essays about his experiences on hashish and opium] … Euphoria and brilliant storms of laughter; ecstatic reveries and extension of one’s personality on several simultaneous planes are to be complacently expected…”

Listed among the ingredients was “a bunch of canibus [sic] sativa,” which Gysin noted might not be easy to come by.

“Obtaining the canibus may present certain difficulties, but the variety known as canibus sativa grows as a common weed, often unrecognized, everywhere in Europe, Asia and parts of Africa; besides being cultivated as a crop for the manufacture of rope. In the Americas, while often discouraged, its cousin, called canibus indica, has been observed even in city window boxes. It should be picked and dried as soon as it has gone to seed and while the plant is still green.”

He also cautioned that this fudge, “should be eaten with care. Two pieces are quite sufficient.”

Publisher Panic

Now, contrary to popular belief, Toklas apparently had almost no knowledge of Cannabis or hashish. In the 2002 book “Kiss Me Again,” Toklas admitted to author Bruce Kellner that she’d never tried marijuana, and that Stein had tried it only once and had disliked how “it disoriented her thinking” and “frightened her.”

Unaware of Gysin’s prank, Toklas naively included Gysin’s recipe and sent it off to the publishers. It was only after Time magazine’s cheeky review appeared in October 1954 — mere weeks before the book’s publication — that she realized what had happened.

“The late poetess Gertrude Stein… and her constant companion… Alice B. Toklas used to have gay old times together in the kitchen,” the review read. “Perhaps Alice’s most gone concoction (and also a possible clue to some of Gertrude’s less earthy lines) was her hashish fudge.”

The publishers were panicked; the U.S. Congress had recently passed the Boggs Act, establishing harsh new mandatory sentences for Cannabis related offenses. Harpers wired the Attorney General’s office to ask if publishing a Cannabis recipe was illegal. It was not, they said, but Harper pulled it from the American edition regardless to avoid any possible liability. The U.K. edition, however, was published unabridged and became an overnight sensation. It was so popular, in fact, that some accused Toklas of including the hash recipe as a publicity stunt.

We Love You, Alice B. Toklas

It wasn’t until the second U.S. edition came out in 1960 that the recipe became available to Americans. That edition was also a smash hit – selling seven thousand copies in the first month and prompting two subsequent printings.

The book became a touchstone of sorts for the burgeoning counterculture – reportedly prompting invitations for Toklas to cook and read at various hippie gatherings, and even inspiring a movie: the 1968 cult classic “I Love You, Alice B. Toklas,” starring Peter Sellers. In this rom-com farce (arguably the first stoner film), Sellers plays an uptight lawyer who converts to freakdom after eating a batch of weed-laced brownies and falling for a beautiful young stoner gal. It’s because of this film that Toklas’ name became synonymous with pot brownies – despite the fact that the confection in her book bears no resemblance to a brownie and contains no chocolate. (The first published recipe for hash brownies actually appeared in 1966’s “The Hashish Cookbook.”)

Nevertheless, by the end of the decade, Toklas had become an unlikely icon of the Cannabis-fueled counterculture. Some have even claimed that the term “toke” was derived from “Toklas (it wasn’t – it comes from the Spanish verb tocar, meaning to “tap” or “hit”).

Death & Legacy

Sadly, Toklas didn’t get to enjoy her hippie hero status for long; on March 7, 1967, just over a year before the release of the film bearing her name, Alice B. Toklas died at the age of 89. She was buried in the same plot as her beloved Gertrude in Paris’ Père Lachaise Cemetery, with her epitaph inscribed inconspicuously on the back of Stein’s headstone.

“The Alice B. Toklas Cookbook” has since become one of the best-selling and most influential cookbooks of all time, earning Toklas a place among the culinary greats. She is also a hero of the LGBTQ+ movement – honored in her hometown of San Francisco with both a political organization (The Alice B. Toklas LGBTQ Democratic Club) and a section of Myrtle Street named after her. And yet, whether justified or not, it’s her reputation as “Mother of the Pot Brownie” for which she’ll always be best remembered.