Functional glass art is a huge part of our culture. Heady borosilicate bongs and bubblers are not only the method by which glass artists express their creativity and earn a living—they’re also a way for us potheads to reflect our personalities through our paraphernalia. Of course, none of the amazing artistry we see today would exist were it not for the Pyrex pioneers who paved the way. And when it comes to glass smokeware, it doesn’t get much more old school than Jerome Baker.

PYREX PIONEERS

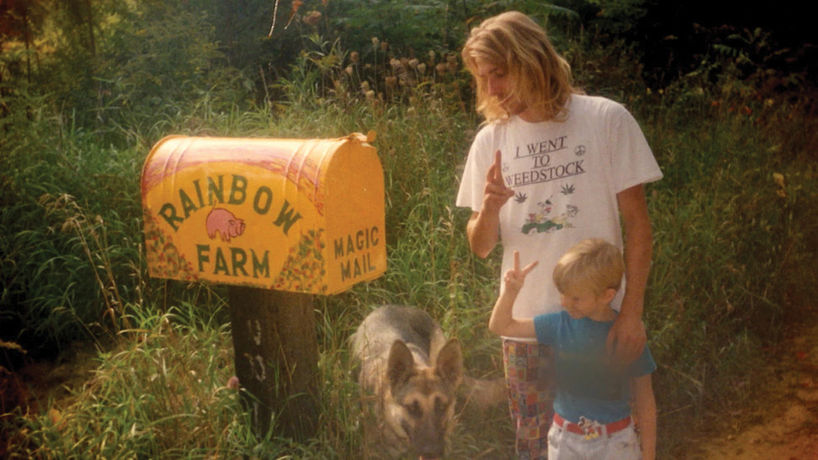

The story of Jerome Baker Designs begins, unsurprisingly, along Shakedown Street in the parking lot of a Grateful Dead show in Foxboro, Massachusetts in July 1989. It was there that a young Deadhead from Miami by the name of Jason Harris—who was attending junior college in the suburbs of Boston—met a bearded hippie from Eugene, Oregon selling glass pipes by the name of Bob Snodgrass. After graduating in 1991, Harris enrolled in the art program at the University of Oregon, moved out to Eugene, and decided to reach out to the pipe maker.

“My first week out there I looked him up in the white pages, called him up, and said, ‘Hey—I just moved here from the East Coast…can I come over and check you guys out?’ And they said, ‘Sure, come over.’ I visited them in their little trailer in Glenwood, Bob had his overalls on… he was the coolest dude I’d ever met. I just wanted to be like him instantly.”

Known as the Godfather of Glass, Snodgrass invented two groundbreaking glassblowing techniques: fuming, aka color-changing glass (spraying precious metals into the glass to create a mirror-like effect as the inside blackens from smoke), and the “pushed-in bowl.” His individualism and ingenuity would inspire and influence all those to follow.

“There was just some magical attraction to Bob—he’s just that kind of being,” Harris says. “It’s like being around a master—not in a technical sense, but in an imaginative sense. It’s more like wizardry.”

In the months that followed, Jason saved his money, bought a torch, and began studying under Snodgrass as one of only ten apprentices.

“There was an energy in the air surrounding that pipe makers’ scene at the time,” he recalls fondly, “something that I would consider akin to when Manet, Monet, and Picasso were hanging out together in Paris, understanding that there’s a movement or a renaissance going on and they were a part of it. It was magical.”

In 1993, Harris and fellow apprentice Chris Shave (founder of Jah Creations Glass) started working together—first at a small garage studio down the street from Snodgrass’ shop, then in a larger studio with another fellow student, Dan K. Dan was the first of the group to earn a formal degree in the art; he’d attended Salem Community College in New Jersey (the only school to offer a degree in scientific flameworking). It was Dan who introduced the group to the big Carlisle CC Burner torch and heavy wall glass tubing, as well as the “wrap and rake” technique—all of which were game-changers for the budding industry. (Sadly, both K and Shave have since passed away).

Harris and Shave would mostly sell their pipes out on Dead tour, as well as at headshops in New York, where oddly they were valued by weight ($10 per gram). Eventually, to set himself apart and earn more money, Harris began making bongs rather than pipes—a technique he learned from Snoddy’s top student, Cameron Tower.

Since his mother was a flight attendant, Harris was able to fly for free, and he took advantage of that privilege to travel the world and learn as much about glass art as possible. He studied and worked at glass shops in Murano, Italy and Wertheim, Germany, and even went as far as India, where he helped establish a glass factory. He also took summer courses at the esteemed Pilchuck glass school in Seattle, where he continued to hone his skills and expand his horizons.

JEROME BAKER IS BORN

Over time, he developed his own production techniques, and in 1995 he and partner Jordan Schefter officially formed their own glass company, which Harris decided to call Jerome Baker Designs—“Jerome,” an homage to Jerry Garcia, who had recently died, and “Baker,” as in someone who gets “baked.”

“I wanted to have a brand name that everybody could get behind—something besides just my own name.”

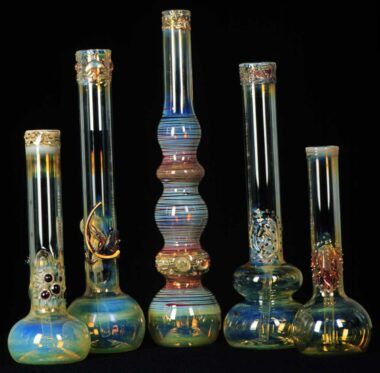

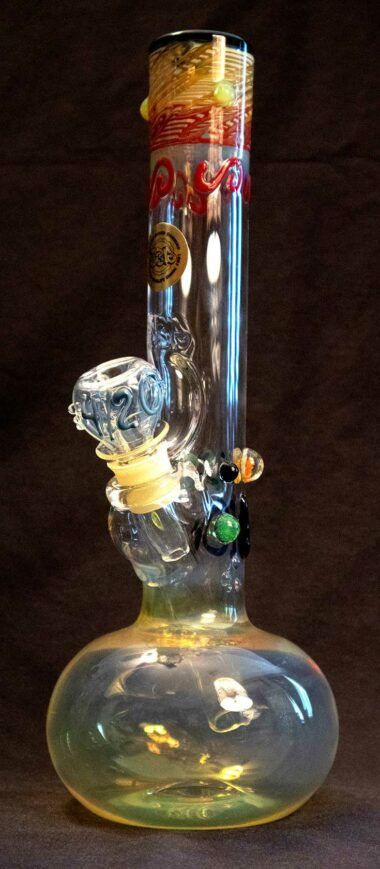

Harris and his team began cranking out pipes and bongs and selling them—where else—on Dead Tour. One of their trademark styles was the Mothership—an orb-like base with a long shaft and a “snap and pull” downstem (a flared tube with a rubber seal that you pull out to carb)—an idea they borrowed from the Graffix bongs of the time.

Unlike heady custom pieces, in which individual artists focus on creating unique works of art, JBD focused on production pieces—meaning that various artists in their shop would work on different components and assemble them in more of an assembly line fashion. This methodology proved highly successful: between 1996-2002, they won five Cannabis Cup awards (including the first-ever Best Glass Cup); by 1999, they’d become the largest smokeware company in the world—employing 70 glassblowers and earning around $4 million a year.

It was during JBD’s heyday in the early 2000s that they produced the bong we have in our museum collection. The base of the tube features a spotted frog and several small bubbles (inside of which are tiny mushroom scenes), and at the top of the tube is a colorful swirly design that includes two dragonflies—all common adornments of their work at the time. Harris had to reacquire it from a private collector in order to provide it to the museum. The piece, which Harris refers to as “a really pure example of the JDB style in Eugene at its height,” was originally sold for around $500, but is now valued at around $8000. This exponential increase in value is true for most of the pieces from this period, which Harris describes as “pre-Op.” What does pre-op mean, you may ask? Keep reading.

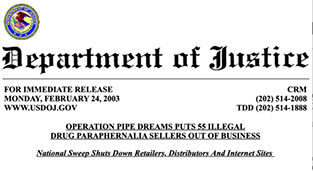

OPERATION PIPE DREAMS

It was around 6 am on the morning of Monday, February 24th, 2003, and Harris was asleep in his bed when he was suddenly awakened by a thunderous pounding on his front door. It was the knock that every cannabis outlaw has dreaded might someday come: the cops. Dozens of DEA agents in full swat gear raided his home, hogtied him, threatened to shoot his dog, questioned him extensively, then hauled him off to county jail—not for possessing or selling any illicit drugs, but merely for selling glass pipes deemed to be illegal drug paraphernalia.

Unbeknownst to him, at the same time they were ransacking his home, they were also raiding his headshop, warehouse, and production facility. In fact, it wasn’t until Harris was in a jail cell watching TV through the bars that he realized the full extent of what had gone down that day. In a news conference held by then-Attorney General John Ashcroft, he learned that his arrest was actually part of a broader, multi-agency sting called Operation Pipe Dreams targeting dozens of paraphernalia producers across the country. (A smaller joint action, codename Operation Headhunter, was also launched the same day—targeting distributors in Michigan, California, and Texas.)

“With the advent of the Internet, the illegal drug paraphernalia industry has exploded,” announced Ashcroft. “The drug paraphernalia business is now accessible in anyone’s home with a computer and Internet access. And in homes across America, we know that children and young adults are the fastest growing Internet users. Quite simply, the illegal drug paraphernalia industry has invaded the homes of families across the country without their knowledge…Today, the Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force…has taken decisive steps to dismantle the illegal drug paraphernalia industry by attacking their physical, financial, and Internet infrastructures.”

“Holy shit,” Harris thought to himself as he watched the press conference, “I’m in serious trouble!”

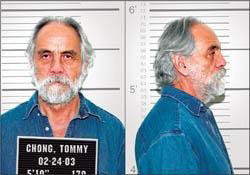

Operation Pipe Dreams was a two-year, $12 million investigation involving 2000 law enforcement personnel that resulted in the indictment of 55 smokeware producers (and another nine resulting from Operation Headhunter). Among those caught up in the dragnet was famed cannabis comedy actor Tommy Chong.

His son Paris’ companies Chong Glass Works and Nice Dreams had been entrapped by undercover agents who eventually pressured them into selling merchandise across state lines despite numerous prior refusals. To spare his wife and son from conviction, Tommy took the full rap—agreeing to plead guilty to one count of conspiracy to distribute drug paraphernalia.

On September 11, 2003, Tommy Chong was sentenced to nine months in federal prison and a year of probation, as well as a $20,000 fine—not to mention the $103,000 in assets that were seized. Of all the individuals charged as part of Operation Pipe Dreams, Chong was the only one to see actual prison time—no doubt intended by the Bush Administration to make an example of him.

“By putting the celebrity in jail, they were using the justice system to make a political statement,” says Harris. “That’s what they did with Tommy.”

PAYING THE PIPER

Thankfully, Harris’s deal, on the other hand, allowed him to avoid jail time. Though he had to pay massive fines and legal fees, he was sentenced to just one year of house arrest and five years federal probation. Nevertheless, authorities confiscated all of his inventory and assets, including his computers and his website, jeromebaker.com. The only thing they didn’t take was his glassblowing equipment, thanks to quick thinking on his part.

“When I was in jail, I used my single phone call to call up my foreman and say, ‘I want you to go down [to the studio] and steal everything that they left.’ So he went and got everything out of there and brought it all to a barn in the middle of Oregon.”

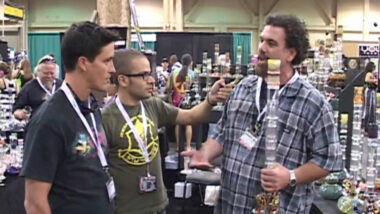

Harris later sold that equipment—along with whatever clothing and other non-paraphernalia merchandise he had left—to help cover his legal expenses and survive during his house arrest and parole. Unfortunately, even that proved to be a challenge: Harris suddenly found himself persona non grata in the glass community, as he learned when he attended the CHAMPS trade show a few weeks after the bust.

“I went to the show to unload the rest of my shirts or whatever other gear I could get rid of to raise money for legal fees, and I got looked at as an outcast,” he laments. “There was a period of years there where I was shunned by the industry because I was ‘hot.’ I felt really rejected.”

DON’T CALL IT A COMEBACK

With pipe making off the table, Harris needed a new way to earn a living. And as the old saying goes: those who can’t do, teach. Without the pressure of having to produce and sell products, he chose instead to explore his technical and artistic skills by accepting a teaching position at his alma mater, the University of Oregon.

“I ended up building out their whole glassblowing program, which is still there today,” says Harris. “I also worked at the Eugene Glass School [of which he’s a founding member] six days a week, making a massive body of work. So I really made the most of my couple of years there in Eugene after the arrest.”

In 2006, after his time at the university (and his house arrest) were up, Harris left Eugene and moved out to Maui to lay low—surfing and creating high-end, non-functional glass art for tourists under a new company called Maui Glass Blowing. But even though JBD was no longer making smokeware, Harris never abandoned the brand. To keep the Jerome Baker name alive, he transitioned it to a skater/surfer lifestyle brand—selling JBD skateboards and clothing in the same smoke shops where he used to sell his glass. While this new direction never really paid off financially, it kept the JBD brand relevant within cannabis culture. And though he continued to make the occasional pipe or bong on the DL using other artists’ studios and equipment, it wasn’t until 2012 that he decided it was time for JBD to make a comeback.

“The decision-maker for me to come back out of the closet so to say was the 2012 High Times Cannabis Cup in Denver, Colorado,” says Harris. “I got a sponsor to bring me out to blow glass at the show, and we smoked recreational cannabis legally on the mainland United States for the first time. After that event, we started working on a plan to develop the brand again.”

In a crazy stroke of luck, his old website site address happened to be available; turns out the government had auctioned off the confiscated URL and he was able to reacquire it for just $700. Using his skills, connections, name recognition, and an exciting new marketing tool called social media, Harris was able to re-established JBD’s place of prominence in the glass industry within just a few years. Before long, they were producing custom pieces for A-list artists, including Slayer, Santana, the Dalai Lama, and even Snoop Dogg, for whom he made an $18,000 stash jar that holds a whole pound of weed.

In 2018, they won two more Best Glass Cups in Northern Cali, then went on to make history months later by creating the world’s largest bongs in Seattle (as documented by Leafly in their short film Redemption Bong). The largest of the batch—dubbed “Bongzilla”—stood 24-feet tall and weighed 80 pounds and made its debut in October 2018 at the Cannabition exhibit in newly legalized Las Vegas.

That same year, JBD also opened their new headquarters in Vegas’ arts district, which they named the Dream Factory—a combination studio, shop, and showroom.

In 2019, Harris was named one of the top 11 artists who changed the glass game by Leafly. Then on April 20, 2020, he was named a 420 Icon by the Cannabis Business Awards (in collaboration with World of Cannabis) and produced the trophy bongs for our virtual event contest winners.

Last fall, JBD released a line of limited edition Chong Bongs with fellow former OPD target Tommy Chong, and are now launching a new web series on YouTube called Operation Pipe Dreamers (a glassblowing competition show that features Chong as one of its judges) in April. According to Harris—who’s now celebrating his 30th anniversary in the business—the show has two main goals: the first is to document glass art for posterity.

“If I make a bong and somebody buys it, nobody else really sees it. If there are no pictures of it, it doesn’t get logged in our history,” says Harris. “Videos give it a legacy that will last…like what you’re doing with Cannthropology. We need to make sure the newbies understand the history behind what’s going on—that the OG vibe gets remembered and embedded into what this culture’s going to become.”

“We need to make sure the newbies understand the history behind what’s going on—that the OG vibe gets remembered and embedded into what this culture’s going to become.”

And the second goal? “To infect the hearts and minds of all Americans” to help finally get cannabis legalized nationwide.

“The reality is, even though I have a permit from the city, manufacturing drug paraphernalia is still illegal on a federal level,” says Harris. “The exact same laws that got me arrested back in 2003 are still on the books today—they can still come bust my doors down at any time. The laws have to be changed.”

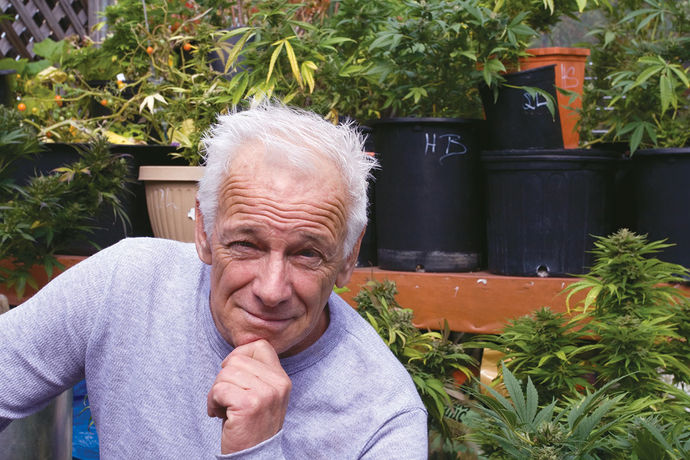

Harris with the Leaf crew.

Bobby Black & Jason Harris

To go behind the glass with Jason Harris check out Episode 10 of our Cannthropology podcast. For more about Jerome Baker Designs visit jeromebaker.com.

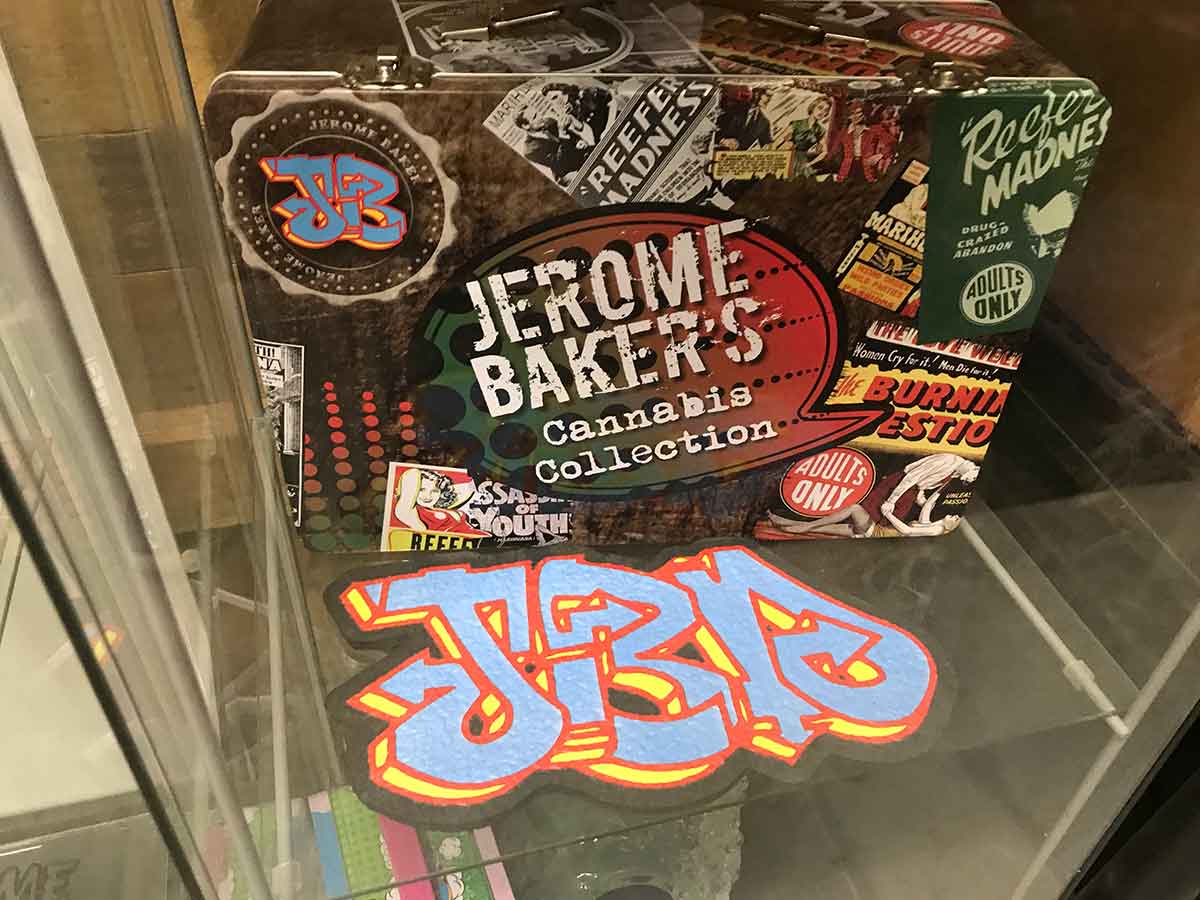

COLLECTION ITEMS:

- Jerome Baker Pre-Op Mothership Frog Bong; 2003; Item #S012

- 420 Icons Contest Winner Giveaway bong; April 20, 2020; Item #S026