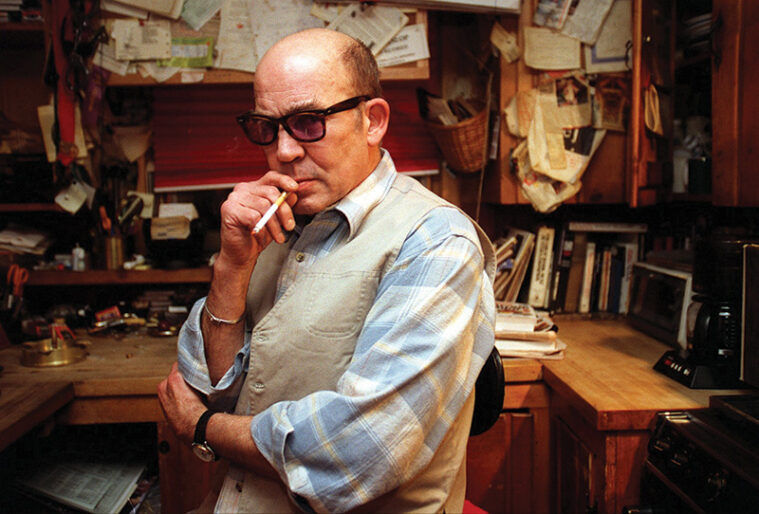

With his trademark sunglasses, cigarette holder, and bald head, and his passion for guns, drugs, whiskey, and weed, author Hunter S. Thompson was essentially a living caricature — an iconoclastic literary figure whose eccentric writing and excessive lifestyle redefined journalism and established him as a hedonistic hero of the counterculture.

Early Years

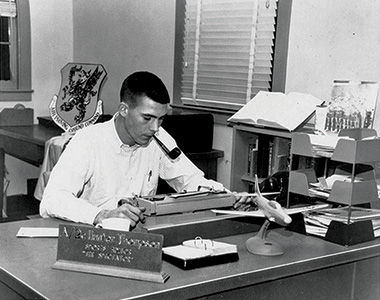

Born on July 18, 1937, in Louisville, Kentucky, Hunter Stockton Thompson displayed passions for writing and rebellion at an early age. After a minor crime spree in his youth, he was sentenced to 60 days in county jail for armed robbery at the age of 17. He was paroled after just 30 days, however, on the condition that he enter the Air Force upon his release; he did, and worked at their newspaper, but was honorably discharged a year early due to “his rebel and superior attitude.”

After leaving the service, he spent several years as a freelance writer, traveling around the Americas and covering an array of topics for various publications. Then, in 1964, he and his new wife Sandra settled near Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, where he was first exposed to the emerging hippie counterculture.

Angels, Pranksters & Acid

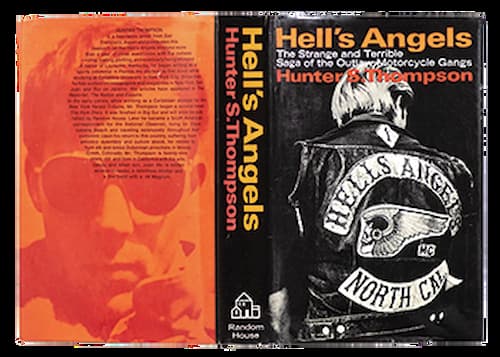

In early 1965, Thompson wrote an article about the Hells Angels biker gang for The Nation, which led to several book offers. As a result, he spent the next year living and riding alongside the Angels through their misadventures. His book, “Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs,” was released in 1967 and was an immediate success.

One of the many escapades detailed in the book is the time that Thompson introduced the Angels to the Merry Pranksters. After meeting Thompson at SF’s public television studio in August 1965, Pranksters co-founder Ken Kesey invited him and the gang to his La Honda home for a huge two-day party the following weekend. It was there that he met LSD guru Richard Alpert and beat icons Neal Cassady and Allen Ginsberg, and where he and the Angels took acid for the first time.

Going Gonzo

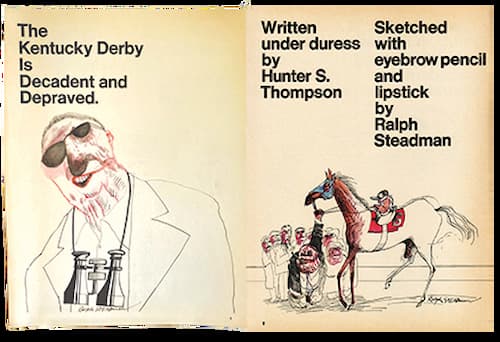

In May 1970, Thompson pitched a story about the Kentucky Derby to a short-lived publication called Scanlan’s Monthly. Since he refused to work with a photographer, the editor hired a British illustrator named Ralph Steadman, who flew over from London and met Hunter at the racetrack. The pair apparently hit it off despite Thompson’s excessive drinking and constant threats to mace people.

Around a week later, with the rest of the magazine already on press and no coherent story assembled, Hunter tore out pages from his notebook and “telecopied” them to the editor — which, surprisingly, they ended up printing word for word. The article “The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved” was a frantic, fictionalized, first-person skewering of Southern culture, perfectly complimented by Steadman’s manic expressionist scribblings. Thompson thought he’d totally blown the assignment; instead, many hailed the piece as “a tremendous breakthrough in journalism, a stroke of genius.” One letter of praise from a Boston Globe editor named Bill Cardoso declared: “This is it — this is pure Gonzo.” Thompson loved the term so much that he adopted it as the name of the new type of journalism he’d invented.

Freak Power in the Rockies

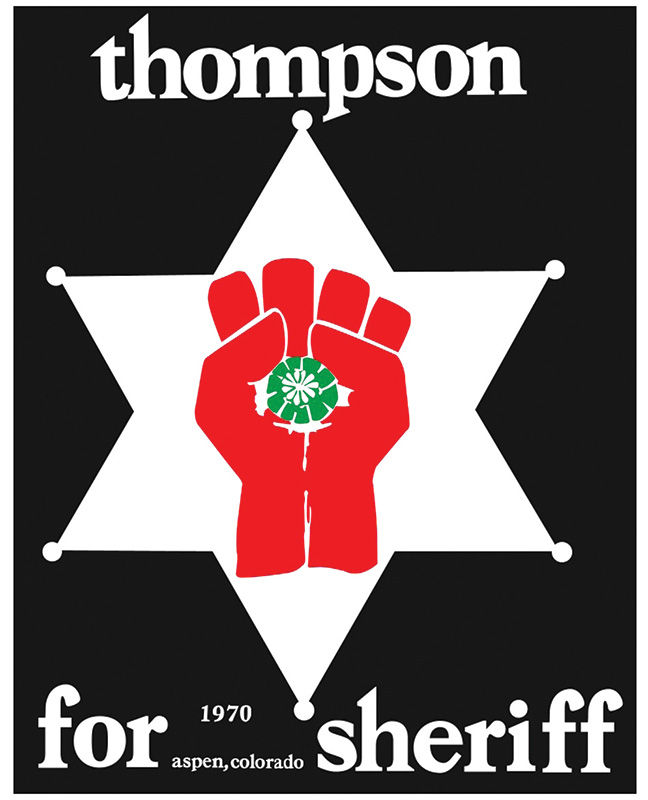

In 1968, Thompson and his family moved to Colorado, where he purchased the 110-acre plot of land in the small town of Woody Creek outside Aspen where he would live for the rest of his life — a “fortified compound” he named Owl Farm. Of course, Thompson was just one of countless intellectuals and hippies who had relocated there during the 1950s and ’60s. Many conservatives there, however, didn’t care for the scruffy new immigrants and began persecuting them. One such resident was business owner turned magistrate Guido Meyer, who hung a “No Hippies Allowed” sign at his hotel and vowed to rid the area of the dirty, dope-smoking longhairs — jailing several of them for vagrancy and other minor offenses.

Now, Thompson never identified as a hippie … but after being brutalized by Chicago PD during the protests outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention, he’d become an avowed avenger for civil rights. And so, he decided to get involved.

In 1969, he persuaded Joe Edwards — a biker/lawyer who defended the arrested hippies — into running for mayor and helped manage his campaign. Then, after Edwards lost (by only six votes), Thompson declared his candidacy for Pitkin County sheriff the following year. He ran on what he called the Freak Power Party ticket — a new organization of his own invention, whose official logo was a two-thumbed fist grasping a peyote button. He detailed the Freak Power platform in his debut article for Rolling Stone magazine entitled “The Battle of Aspen” — a catalog of controversial campaign promises that included disarming the police, locking “dishonest dope dealers” up in stocks in front of the courthouse, and decriminalizing personal use and possession of marijuana and other drugs.

He didn’t win the election, but his campaign catapulted him into a national media spotlight.

Fear and Loathing

Rolling Stone published many collaborations between Thompson and Steadman in the years that followed, the most famous of which was “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream.” Originally featured as a two-part story in the November 1971 issue (then expanded into a book the following summer), this gonzo masterpiece chronicled the deranged, drug-drenched exploits of Raoul Duke (Thompson) and his attorney Dr. Gonzo (his lawyer friend Oscar Zeta Acosta) during two consecutive trips to Sin City in the spring of 1971. On the second visit, Thompson even attended a narcotics law enforcement conference whose keynote speaker was drug “expert” Professor E.R. Bloomquist, MD — author of a book titled “Marijuana” that claimed to “tell it like it is.”

“The reefer butt is called a ‘roach’ because it resembles a cockroach …” Thompson says Bloomquist purported. “‘What the fuck are these people talking about?’ my attorney whispered. ‘You’d have to be crazy on acid to think a joint looked like a goddamn cockroach!’”

NORML and High Times

It was in 1972, while covering the Democratic National Convention in Miami Beach, that Thompson first met fellow Cannabis advocate Keith Stroup — founder of the recently formed National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML). In his 2013 book “It’s NORML to Smoke Pot,” Stroup tells the tale of how he followed the smell of marijuana below the convention center bleachers, where he found Thompson toking up. After introducing himself, Hunter shared the joint with him, thus beginning a 33-year friendship. At Stroup’s invitation, Thompson joined NORML’s board of directors and attended many of their conferences in Washington, D.C., helping to boost the group’s counterculture cachet.

“Attendance would sometimes increase as much as 50 percent when word spread that Hunter would be there,” says Stroup. “People brought their best weed from around the country just for the chance to share it with Hunter S. Thompson.”

In fact, Stroup recalls one time at the 1977 conference when attendees began throwing joints at Thompson during a panel after he sarcastically chided them for celebrating a minor political win.

“I don’t know what all you people are so happy about,” Thompson reportedly barked. “How can you be in such a good mood when I can’t find any marijuana? All the progress that you’re talking about doesn’t mean shit if marijuana smokers can’t get good marijuana!”

Through Stroup, Thompson also developed a relationship with High Times magazine — doing several interviews and appearing on their cover twice. For the “Celebrities on Pot” piece in their 20th-anniversary issue, Thompson told HT:

“I have always loved marijuana. It has been a source of joy and comfort to me for many years. And I still think of it as a basic staple of life, along with beer and ice and grapefruits — and millions of Americans agree with me. I am not an addict, but I refuse to be without it … marijuana’s gotta be there. I can’t talk about giving up weed.”

Success, Suicide & Sendoff

In the decades that followed, Thompson’s counterculture cred continued to grow as he embarked on a series of college lecture tours, wrote nearly 100 articles, and published around a dozen books — some of which were adapted into feature films: “Where the Buffalo Roam,” “The Rum Diary,” and “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.” Acclaimed Doonesbury cartoonist Garry Trudeau based his character “Uncle Duke” on him, and several filmmakers have released documentaries about him. By the turn of the millennium, Hunter had cemented his status as a literary icon. But despite his outward success, Thompson was suffering internally — both from “unbearable” pain from injuries that had confined him to a wheelchair and from depression. Finally, one Sunday afternoon, he decided he’d had enough.

At 5:42 p.m. on February 20, 2005, while on the phone with his wife, Hunter S. Thompson held a .45-caliber handgun to his head and pulled the trigger. Though distressing, his suicide was far from unexpected or out of character: his second wife Anita said that he’d talked about killing himself in the months leading up to the incident, saying that he “wanted to leave on top of his game.” And that was hardly the first time.

“He told me 25 years ago that he would feel real trapped if he didn’t know that he could commit suicide at any moment,” Steadman wrote in his 2006 memoir “The Joke’s Over: Bruised Memories — Gonzo, Hunter S. Thompson, and Me.” “I don’t know if that is brave or stupid or what, but it was inevitable.”

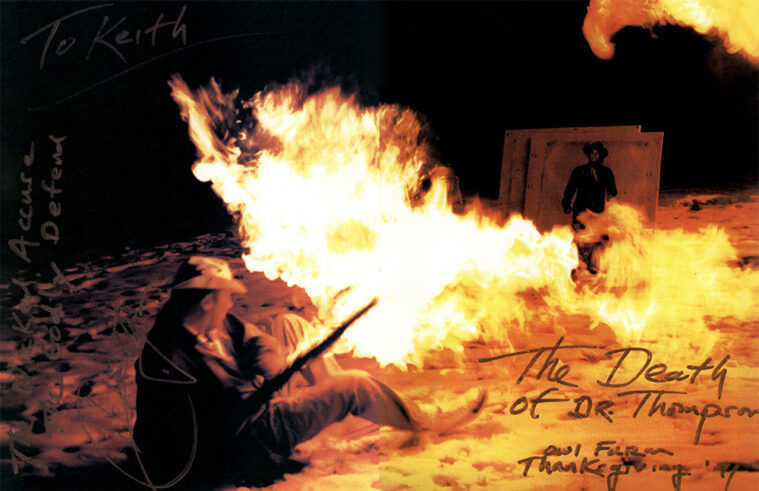

In fact, he and Steadman had already planned his funeral almost 30 years earlier — designing a cannon in the shape of his gonzo fist logo from which he wanted his mortal remains to be fired. And thanks in part to his pal Johnny Depp (who portrayed him on screen), those wishes were ultimately fulfilled: on Saturday, August 20, 2005, at a private ceremony on Owl Farm dubbed “Hunterpalooza,” Thompson’s ashes were launched into the night sky from atop a 153-foot-tall Freak Power tower.

Epilogue

Since his passing, Hunter’s widow has founded the nonprofit Gonzo Foundation, dedicated to promoting literature, journalism and political activism. She announced a Gonzo Cannabis brand featuring strains cloned from samples of Hunter’s head stash and established two scholarships in his name. NORML has also set up a scholarship in Thompson’s name, awarded him a Special Appreciation Award posthumously, and named their annual Media Award after him.

But beyond all the articles and accolades, perhaps Hunter’s greatest legacy is the countless writers and journalists—myself included—he inspired to trust their inner voices, color outside the lines, and let their freak power flags fly. After all, as he famously once said, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.”