Twenty-two years ago this month, two gay Cannabis activists – Tom Crosslin and Rollie Rohm – were gunned down by police on their farm in Vandalia, Michigan, after a five-day siege that some have called “The Waco of Weed.”

Tom & Rollie

Grover “Tom” Crosslin loved weed from an early age. After first getting high with his brothers when he was just 14, Cannabis quickly became a normal part of their family life.

After dropping out of high school, Crosslin worked various blue-collar jobs before becoming a real estate developer – fixing up run-down properties and flipping them or renting them for profit. It was through his construction company that he met the love of his life: an easy-going young crewmember named Rolland “Rollie” Rohm. Though the two men were very different – Rollie, a slim, quiet, longhaired hippie, and Tom, a bear-like hothead nearly 20 years his senior – they instantly connected and began a romantic relationship.

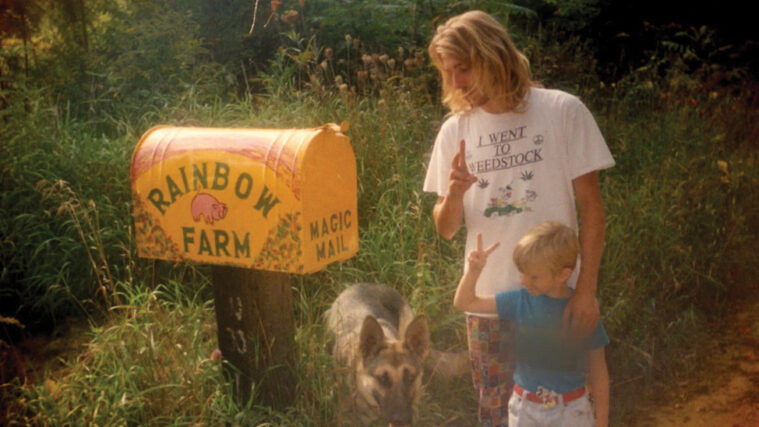

Though barely 17 when he met Crosslin in 1990, Rohm had already been married and fathered a son named Robert. In 1993, after helping Rollie gain custody of Robert, Crosslin purchased a 34-acre farm in rural Vandalia, Michigan to serve as his new family’s home. During one of the countless weeks they spent renovating the property, they saw so many rainbows that they decided to name their new home Rainbow Farm.

Over The Rainbow

Tired of managing his many properties, Crosslin decided to turn Rainbow Farm into “an alternative campground and concert arena” and spent the next few years (and nearly half a million dollars) transforming the farm’s open spaces and overgrown cornfields into one of the top pot destinations in the nation. Crosslin and his team constructed several structures, including an outdoor stage, a ticketing booth, a large main building to house their offices and shops, and amenities for campers. They then set about bringing his dream of a stoner utopia to life.

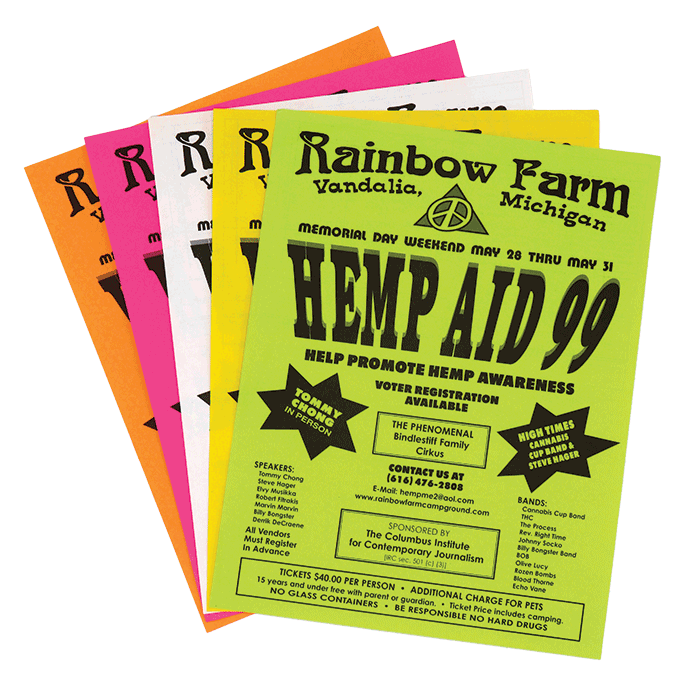

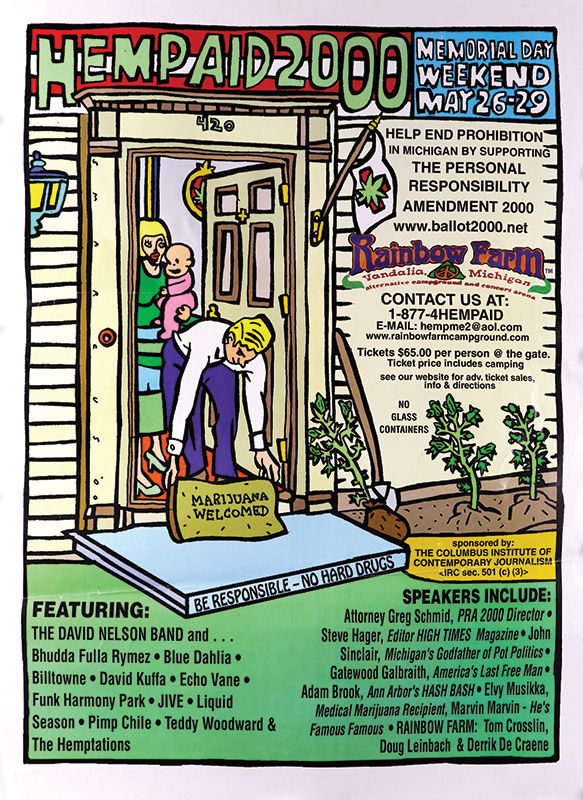

Starting in 1996, Rainbow Farm began hosting two annual festivals: Roach Roast on Labor Day weekend and Hemp Aid on Memorial Day weekend, as well as other various events in between. Described as “part Woodstock, part union picnic” by “Burning Rainbow Farm” author Dean Kuipers, these festivals included food, drink, activism and entertainment. Among the prominent performers and activists who attended these events were Tommy Chong, Big Brother and the Holding Company, The Byrds, country music star Merle Haggard, High Times editor-in-chief Steve Hager, and activist legends John Sinclair and Jack Herer. In addition to speeches and voter registration drives, they collected thousands of signatures for the Personal Responsibility Amendment in 2000 – a ballot initiative to legalize possession of three plants and three ounces of Cannabis for adults. Soon, Rainbow Farm became the center of Cannabis activism in Michigan.

At its peak in 1999, Rainbow Farm had nearly 3,000 attendees – but despite their popularity, the events never turned a profit. For Crosslin it was never about money, but about providing a space of safety and freedom for Cannabis smokers.

Legal Problems

Unfortunately, Crosslin’s pro-pot protestivals encountered serious pushback from law enforcement – namely, Cass County’s conservative prosecutor, Scott Teter, who launched a vendetta of litigation and intimidation against Rainbow Farm.

From 1997-1999, Teter filed several injunctions against the farm, but Crosslin managed to keep one step ahead of him. Unable to stop the events through the courts, Teter established a drug task force and set up roadblocks leading into the farm to stop and harass festival goers – a move that scared many potential attendees off.

He also sent his narcs into the events (who made numerous drug buys there), but were never able to tie Crosslin or his employees to anything illegal. Nevertheless, in March 1999, Teter sent Crosslin a letter stating that he had evidence of drug sales on the property and that as soon as he could link Crosslin to them, he would take his farm away (under the Drug War’s civil forfeiture laws). The threat of losing his land infuriated Crosslin, prompting a heated and foreboding reply:

“We are all prepared to die on this land before we allow it to be stolen from us,” Crosslin wrote. “How should we prepare to die? Are you planning to burn us out like they did in Waco, or will you have snipers shoot us through our windows like the Weavers at Ruby Ridge? You will have the blood of a government massacre on your hands.”

Raid & Rebellion

Finally, in 2001, Teter found his excuse to bust Crosslin. Apparently, a woman who’d worked for them told authorities that Crosslin was paying employees off the books – allowing Teter to get a search warrant on a trumped-up tax fraud charge. In the pre-dawn hours of May 9, state troopers in tactical gear and automatic weapons raided the farm. Once inside the house, they found over 200 young Cannabis plants in the basement and several loaded firearms, which Crosslin wasn’t permitted to own due to a past gun conviction. Tom and Rollie were both charged with felony cultivation and weapons possession, as well as running a “drug house.” Altogether, Tom was facing up to 20 years in prison. The court also issued an injunction banning any more events on the farm, and Teter filed a request to seize the property. And cruelest of all, on May 15, Teter also had their 12-year-old son Robert taken away and placed in foster care.

Despite everything, or perhaps because of it, Crosslin announced on their website that they’d still be hosting their annual Labor Day party, as well as another small gathering on August 17 – both in defiance of the court order. Two of the few dozen people who showed up to that gathering were undercover cops who were allegedly offered weed. This prompted Teter to petition to revoke the couple’s bail, and a hearing was scheduled for August 31.

Under Siege

The end was drawing near for them, and Crosslin apparently knew it – confessing to his property manager Doug Leinbach: “I’m going to die on my farm, not in prison.” During the last week of August, Tom and Rollie composed handwritten wills – leaving all of their possessions to Rollie’s son Robert – then started giving away stuff from the shops.

When August 31 arrived, Tom and Rollie never showed up in court for their hearing. Instead, they went around the property kicking out the remaining campers and setting fire to the farm’s structures – reasoning that if the government was going to seize his land, he’d “make sure there was nothing left on it.”

Around noon, when a local TV news chopper flew overhead to get footage of the fires, Crosslin – possibly thinking it was a police copter – allegedly shot at it. After that, the FBI was called in, along with SWAT teams, helicopters, surveillance planes and light-armored vehicles (LAVs), all of which surrounded the property – including three FBI sniper teams in camouflage laying in hiding in the woods to monitor the house.

Throughout Labor Day weekend, Tom and Rollie continued burning down structures until the only building left standing was the farmhouse, where they hunkered down for the standoff. Since the police refused to allow Crosslin to talk to Robert or the media, he refused to talk to them. To keep them from moving in, he shot at their vehicles, into the woods, and even at speakers they’d set up to speak to him.

The Massacre

On the afternoon of Monday, September 3, Crosslin walked to a neighbor’s house for supplies. On his way back, he spotted one of the snipers lying on the ground and allegedly raised his rifle (though his friends and family dispute that claim), at which point two snipers opened fire, killing him instantly.

After informing him that his partner was dead, authorities maintained a dialogue with Rohm into the night … until just after 3:00 a.m., when he presumably fell asleep. At that point, they decided to “wake [Rohm] up” by firing a few “dummy rounds” through the windows. Rohm resumed negotiations and agreed to surrender at 7:00 a.m. on one condition: that his son be brought to the farm so he could say goodbye before being taken into custody, which police agreed to. But sadly, that peaceful resolution was about to go down in flames – literally.

Around 6:00 a.m., a fire somehow broke out on the house’s second floor. Authorities blamed Rollie for the blaze, supposing he was finishing what Tom had started … but friends and family accuse police of starting the fire by shooting a flashbang grenade in there to flush Rollie out. In any case, Rohm emerged from the house half an hour later wearing fatigues and allegedly holding a rifle. Through the smoke, officers claim they saw him pointing the rifle toward them and fired several rounds – one of which went right through the stock of his rifle and into his chest. Despite having an ambulance sitting at the ready just outside the farm, friends claim that police allowed Rollie to lie on the ground for over 40 minutes and bleed to death.

When he was killed, Tom Crosslin was 46 years old; Rollie Rohm was just 28.

The Aftermath

Unfortunately, the story of Rainbow Farm never got the national press it deserved since the terror attacks of 9/11 happened one week later – eclipsing all other news stories for many months after.

So what happened to Rainbow Farm after Tom and Rollie’s deaths? Instead of going to their son Robert as the couple intended, it was confiscated, broken up into six parcels, and auctioned off to various buyers with the stipulation that they couldn’t turn the land into campgrounds or throw events there. But in 2012, after changing hands several times, the property was purchased by a farmer/engineer named Gary Healy – who has since reopened it under the name the New Rainbow Farm.

Though Tom and Rollie are now honored with memorial sites on the property, the greatest tribute to their courageous lives is the continuation of their legacy: Rainbow Farm is once again hosting 420-friendly concerts and festivals (with help from their son Robert and Tom’s nephew Boss) with vendors selling Cannabis that – thanks in part to their sacrifices – is now legal in the state of Michigan.