It’s clear the drug war is a scam. The pop-history of Reagan’s “Just Say No” fails to paint a complete portrait of America’s anti-drug ethos. It even predates Nixon’s vapid fear of LSD and naked hippies, and Harry Anslinger’s racist weed propaganda of the ’30s. America’s drug phobia – and specific hatred of Cannabis – began when an influx of Mexicans migrated into the U.S. to flee the Mexican Revolution in 1910. Many brought Cannabis with them over the border, making it a target of racist demonization by the U.S. Government.

Mexicans have a storied history with the plant in the United States. What’s more, the 2020 Census reported that 39 percent of California’s residents are Latinx. Despite technically accounting for the largest portion of the state’s population, relatively no Cannabis brands cater to the Latinx demographic. Sure, there are a few big Latinx names in Cannabis – such as Sherbinski, Berner and B-Real. But they aren’t necessarily making products for the Latinx community.

“When we asked our brand partners why there are no Latino brands, they said because everyone lacked the authenticity to do it, and everything in branding is about authenticity,” says Jesus Burrola, CEO of POSIBL, a 12-acre greenhouse cultivation project in Salinas, Caif. – wholly owned, operated and funded by Latin Americans. “My clients kept asking me, ‘Why don’t you do it?’”

Burrola, who was born and raised in northern Mexico, says he never intended to dive into the branding side of Cannabis. But he realized the large-scale Latinx weed brand wouldn’t materialize unless his team did it. In early 2022, POSIBL launched Humo (meaning “smoke” en español) with an array of aptly named cultivars, including Pastelito (“little cakes”) and Cajeta in honor of one of Mexico’s most beloved goat’s milk caramel confections. Humo is one of the first Mexican American brands available throughout California that’s not only targeting the Latinx demographic but also creating an authentic cultural aesthetic of proud Latinx stoners – sans the cartel and gang stereotypes.

“Just because our brand is Latino-owned doesn’t mean that it’s automatically associated with the cartels,” says Susie Plascencia, brand partner for Humo and Cannabis entrepreneur who’s devoted to dismantling Cannabis’ stigma in the Latinx community. “Part of our mission with the community we are building on social media is making sure people see [the plant] for what it is, which is medicine. It’s something to help the community. So much of the normalization and de-stigmatization happening in the Latino community is coming through the relieving of pain.”

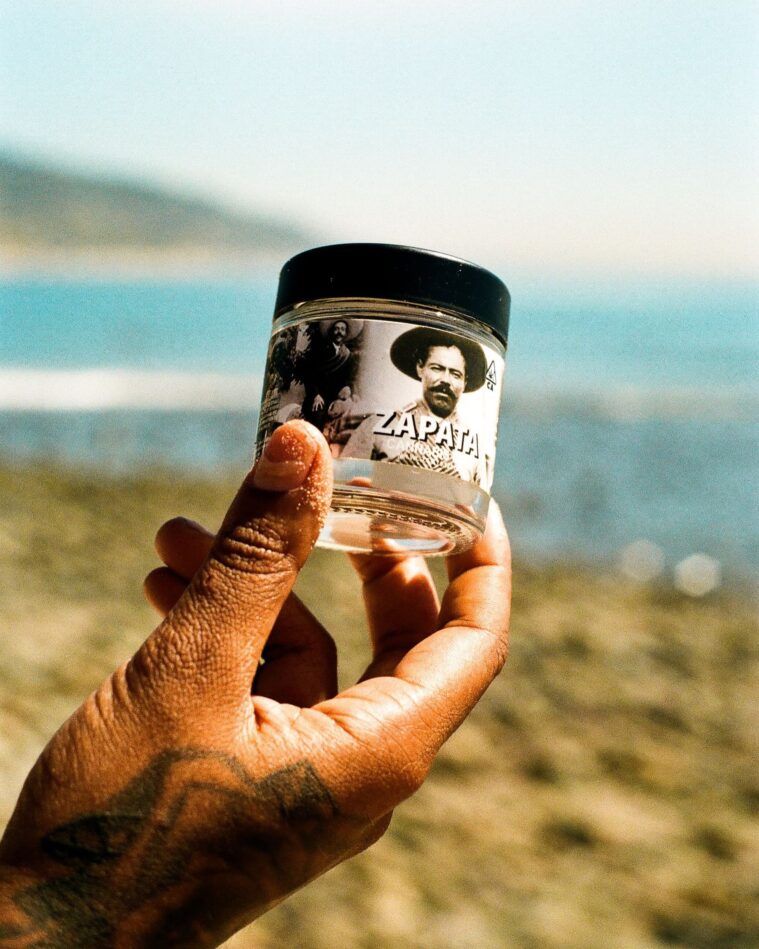

Roni Melton, founder of Zapata Cannabis Co., says non-Latinx people often make inaccurate assumptions that Mexicans in Cannabis are connected to drug kingpins akin to Pablo Escobar or Griselda Blanco. But the stereotyping sometimes extends beyond the shadows of the cartel and into fictionalized, two-dimensional cartoon characters. “This is why our brand is focused on Mexican and minority revolutionaries,” says Melton, referring to Zapata’s strains named after Geronimo, an Apache warrior born in northern Mexico that’s now New Mexico, and Pancho Villa. “People within the culture often don’t know that Emilio Zapata, our namesake, was a hero in the Mexican Revolution and will ask if he’s the Tapatio man! That’s where education comes in.”

Low-quality flower is another Mexican/Cannabis stereotype. But that gets squashed quickly as soon as products come out of the packaging. Humo, for instance, sells clean greenhouse bud grown under the Monterey County sun, with THC percentages in the 30s. Zapata Cannabis Co. sells premium indoor flower with THC also in the 30s. Neither brand sells seedy weed that smells like sun-bleached hay scraps. “Selling really high-quality weed at affordable price points is how you break the stigma of ‘Mexican dirt weed,'” says Melton.

Latin American representation in the global Cannabis industry is growing via education groups, cooperatives and nonprofits. There are groups in New York, such as the Latino Cannabis Association, the Latino Cannabis Industry Association, and High Mi Madre. There’s Cannalatino in Denver, the Bay Area Latino Cannabis Alliance (BALCA) in Oakland, Fundación Daya in Santiago, Chile, and Mama Cultiva in Buenos Aires, Argentina. There are several Latin American-owned dispensaries, too – from Javier’s Organics in Oakland to La Mota in Oregon to Bwell Healing Center in Puerto Rico – all of which are dedicated to the same thing: repairing the damage of vilification.

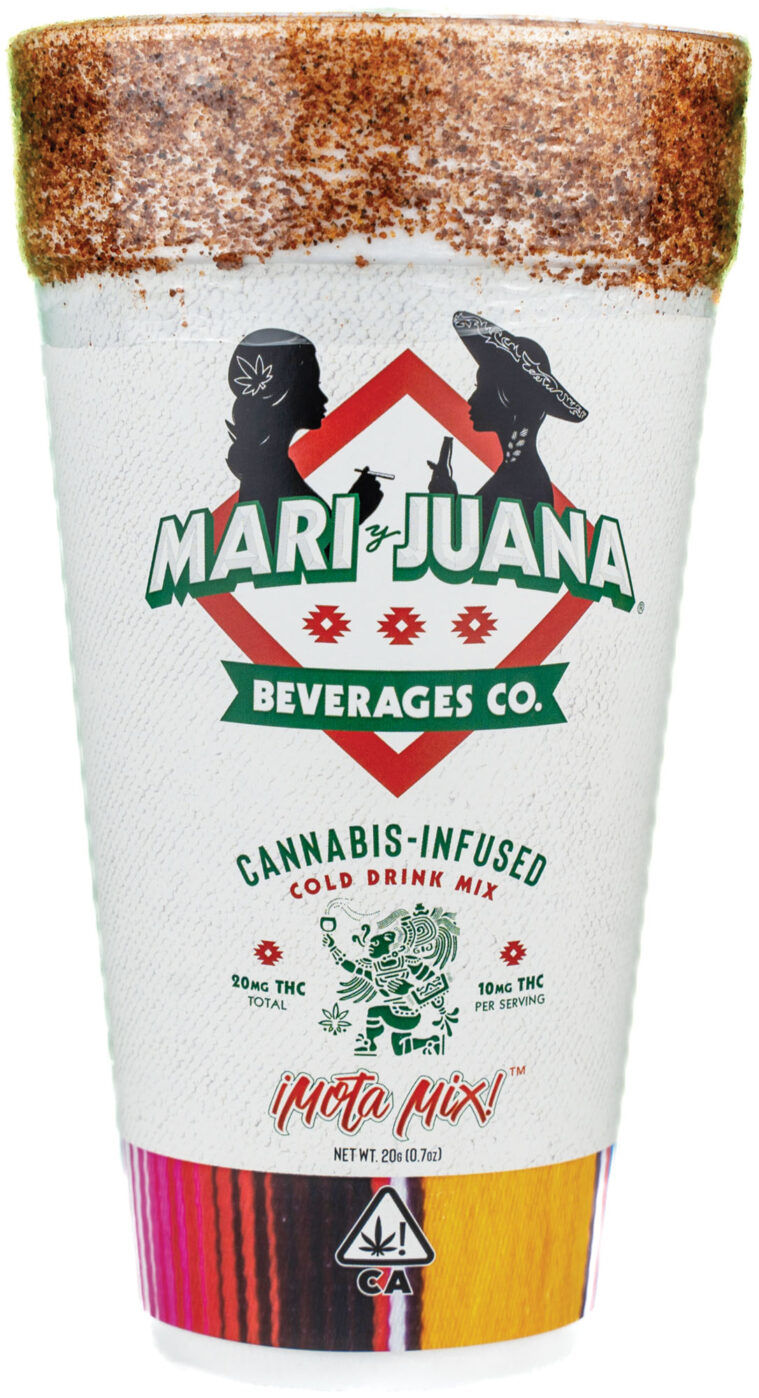

Reclamation of demonized words and symbols is how Daniel Torres, Founder and CEO of Mari y Juana (a California edibles and infused-drinks brand) is educating the public about Cannabis’ Latinx roots.

“We were told that the word ‘marijuana’ was used with racist rhetoric in the early days of Cannabis prohibition,” Torres says. “It was used to demonize Mexican and Filipino immigrants and other people of color. I learned from researching it that, in Mexico, the Spanish word used was ‘marihuana,’ and it wasn’t a bad word. I want to take control of the word and reclaim it to show people that it’s not racist and that it was our word to begin with.”

Torres’ family is from Jalisco, Mexico, where their Indigenous lineage dates back centuries. He pays homage to his ancestors by incorporating Mexican art and food traditions into the products – from branding aesthetics to edible flavors. Mari y Juana’s ¡Mota Mix! is among the most popular infused drink in their lineup. It was a legacy market favorite before Torres and his team jumped into the legal game. Now Mari y Juana offers infused tamarindo, piña, mandarín and guava soft drinks.

“Mari y Juana is here to represent Mexicans and people of Mexican descent in the California Cannabis industry,” Torres says. “It’s a representation of history and tradition. Through our brand and product offerings, we want to share our traditions and history with everyone. I feel Mexican culture is meant to be appreciated by all.”

And so is Cannabis. It looks like Mexicans and marijuana were always meant to be.

Posiblproject.com | @posiblprojec