The Long, Strange Trip

Generally speaking, rock and roll and drugs go together like peanut butter and jelly. But when it comes to psychedelics specifically, there’s no band whose music and history are more steeped in LSD than the Grateful Dead. Here’s a brief look back at how the Dead helped spark America’s entheogenic awakening and forever change Cannabis culture.

Birth of the Dead

The story of the Grateful Dead begins with its most iconic member, the late, great Jerry Garcia.

Born on August 1, 1942, in San Francisco, Jerome John Garcia attended what is now the San Francisco Art Institute, where he was first introduced to beatnik culture. At the age of 11, he discovered rock and roll. Then, on his 15th birthday, his mom bought him an accordion, which he persuaded her to exchange for an electric guitar. That same year, he also smoked marijuana for the first time.

In April 1961, Garcia (now 18) befriended a musician/writer named Robert Hunter and began performing with him around Palo Alto. The following year, Hunter volunteered for the CIA’s covert experiment, MK Ultra, at nearby Stanford University, where he was paid to take psychedelic drugs like LSD, psilocybin and mescaline and report on his experiences. Other participants in the program included Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and novelist Ken Kesey. Kesey began hosting parties at his home in Menlo Park, where he would offer attendees drugs he smuggled out of the program. It was at one of these parties in 1962 that Garcia met Phil Lesh and where (in 1964) he first tripped on LSD — an event that he would later describe as “the single most significant experience in my life.” Garcia apparently loved acid so much, in fact, that he was given the nickname “Captain Trips.”

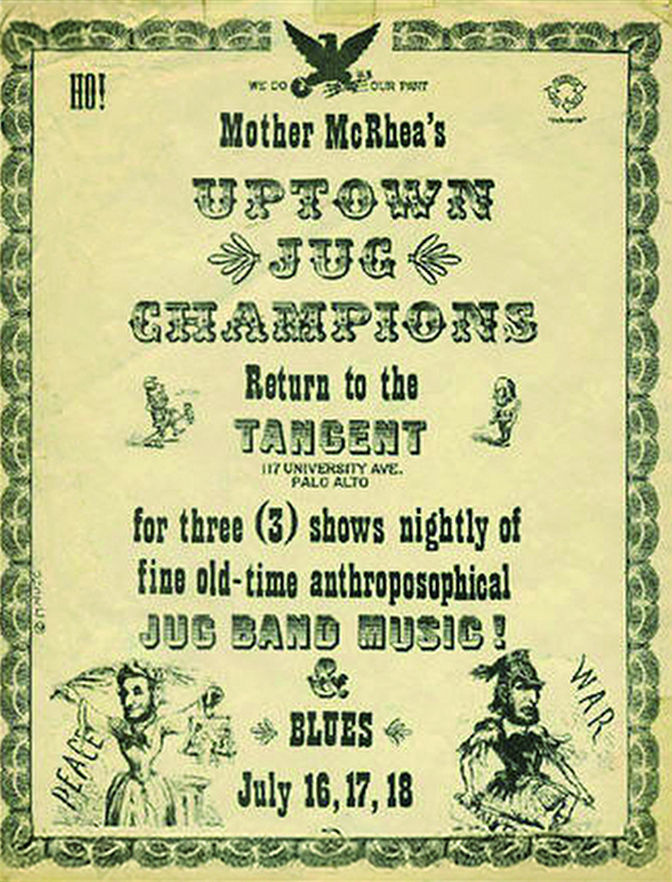

In 1963, Garcia formed a bluegrass band called Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions, featuring a 16-year-old folk guitarist named Bob Weir and a vocalist/harmonica player named Ron “Pigpen” McKernan. After The Beatles’ 1964 arrival in America, the band went electric, added Bill Kreutzmann on drums and Lesh on bass, changed their name to The Warlocks and began gigging around the area. As their weed and acid intake increased, they developed a unique improvisational rapport and a level of notoriety throughout the Bay Area. There was only one problem: In November 1965, they learned of another band in Massachusetts already calling themselves The Warlocks and realized they needed a new name.

One night, while allegedly high on DMT at Lesh’s house, Garcia opened up a 1956 edition of Funk and Wagnall’s “Standard Dictionary of Folklore, Mythology and Legend” to a random page, dropped his finger down onto an entry, then turned to Phil and said, “Hey, man — how about the Grateful Dead?”

The Acid Tests

The same month that The Warlocks changed their name, Kesey also came up with a name for his psychedelic shindigs: the Acid Test.

The first official Acid Test took place on November 27, 1965, at Merry Prankster Ken Babbs’ house. Garcia and the boys reportedly attended, but didn’t play together. It wasn’t until the next Acid Test in San Jose on December 4 that they performed as the Grateful Dead for the first time. After that, they became the house band for all of Kesey’s events — providing the sonic backdrop for these mass multimedia events that featured strobe lights, video projections, poetry readings by Ginsberg and Neil Cassady and vats of “Electric Kool-Aid” spiked with acid. Tripping on acid sometimes meant the band didn’t play well, or even at all … but it also inspired some epic improvisational jams.

“What the Dead learned and experienced at the Acid Tests was that everybody could solo simultaneously, and that it could work,” Grateful Dead archivist Nicholas Meriwether expounded to Collectors Weekly in 2015. “The Acid Tests were the laboratory, the space for them to really see what was possible.”

Among the Dead’s biggest fans was outlaw chemist Augustus Owsley “Bear” Stanley III. Upon first hearing them at an Acid Test at Muir Beach in December 1965, Stanley was immediately entranced, reportedly calling them “magic personified” and “the most amazing group ever.” He volunteered to become their sound engineer and built them a massive speaker system that came to be known as the “Wall of Sound.” More importantly, though, Stanley was the first person to illegally manufacture his own LSD, allowing him to not only supply the band (and the Pranksters) with acid but also use proceeds from the drug’s sales to back them financially.

Hitting the road

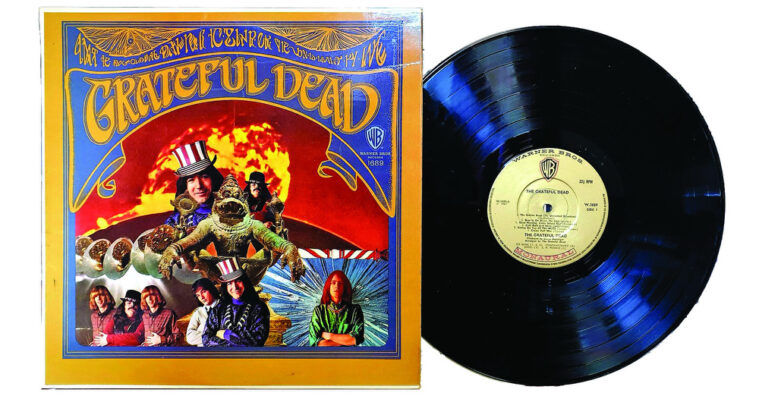

In December 1966, the band signed with Warner Bros., and within weeks, they recorded their self-titled debut at LA’s RCA Studios. By then, the Dead and the Pranksters had already drifted apart (Kesey’s sidepiece, Carolyn Adams, aka “Mountain Girl,” had left him for Garcia), and for some of them, the love affair with acid was wearing off.

“By the first album, we had moved past our psychedelic era. We had gotten to a point of diminishing returns after taking acid for a couple of years,” Weir told Guitar Player in 2022. “We didn’t turn our backs on it so much as we started looking in other directions.”

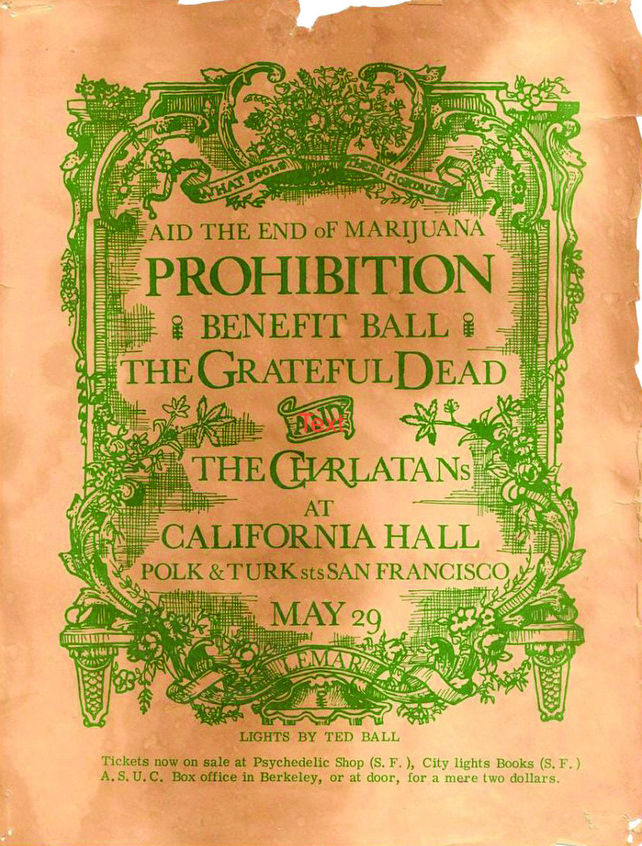

During the late 1960s, the Dead performed at numerous historic concerts. In 1966, there was the End of Marijuana Prohibition Benefit Ball on May 29 at California Hall. In 1967, there was the Human Be-In on January 14 in Golden Gate Park and the Mantra-Rock Dance on January 29 at the Avalon Ballroom. During the Summer of Love, they played the Yippies’ first Smoke-In rally on June 1 in New York City’s Tompkins Square Park and the Monterey Pop on June 18, alongside The Who and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. And of course, there was Woodstock in August 1969.

Raid in the Haight

When not on the road, the Dead resided at their communal home/headquarters in the Haight: a purple Victorian boarding house at 710 Ashbury Street where fellow freaks would frequently pop in to drink, jam and get high — just the kind of activity that tends to draw unwanted attention from the law.

On October 2, 1967, a swarm of police and news media raided the Dead’s residence — busting down the door (apparently without a warrant), reportedly confiscating over a pound of weed and hash, charging each of the occupants with possession and hauling them off in a paddy wagon. The group spent six hours in jail before being released on $500 bail each. A few days later, the band held a press conference in their living room, where manager Danny Rifkin read a statement condemning America’s unjust Cannabis laws:

“The arrests were made under a law that classifies smoking marijuana along with murder, rape and armed robbery as a felony,” he declared. “Yet almost anyone who has ever studied marijuana seriously and objectively has agreed that marijuana is the least harmful chemical used for pleasure and life-enhancement.”

Although initially charged with felonies, most defendants later pleaded guilty to lesser charges and were sentenced to a year’s probation and fines of only $100-$200.

Sadly, that wouldn’t be the Dead’s only run-in with the law.

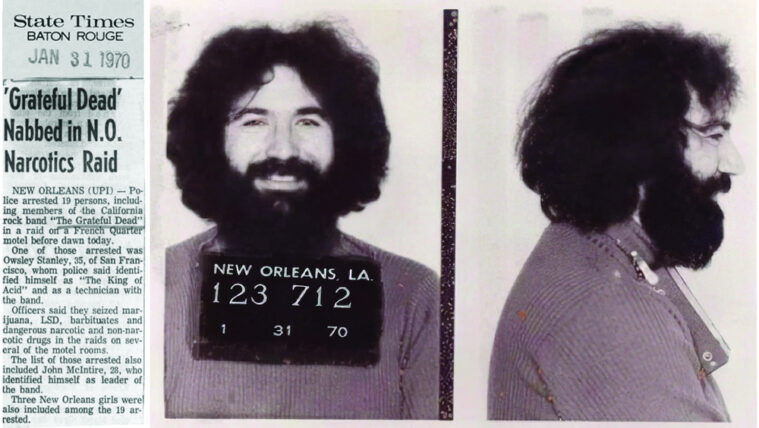

Busted on Bourbon Street

In late January 1970, the band was in New Orleans performing with Fleetwood Mac for the opening weekend of The Warehouse. Late at night after their first show, police raided their Bourbon Street hotel, searching their rooms and arresting 19 members of the band and crew for possession of “some combination of marijuana, LSD, barbiturates, amphetamines or other drugs.”

After spending eight hours in jail, they were all released on bail for the sum of $37,500 — their entire take from the gig. With their cash depleted, the band added a third show on February 1: a fundraising gig dubbed “Bread for the Dead.” Luckily, most of the charges would later be dismissed (except for those against “Acid King” Stanley, who ended up spending two years in prison). That November, the Dead immortalized the incident in their hit song “Truckin’”:

“Busted, down on Bourbon Street / Set up, like a bowlin’ pin / Knocked down, it gets to wearin’ thin / They just won’t let you be, no.”

Weed, Waldos and glass

Over the decades, the Grateful Dead toured constantly, and the community that developed around their concerts helped shape Cannabis culture in a plethora of profound ways.

In 1973, the band launched their own record label (Grateful Dead Records) and several other businesses, all of which were operated out of properties in San Rafael acquired for them by a real estate agent named Gravitch. The band would often offer free tickets and backstage passes to Gravitch’s teenage son, Mark, and his group of friends, who called themselves The Waldos. Since The Waldos would meet after school to get high together at 4:20 pm, they adopted “420” as their secret code for weed. It was from them that the term disseminated into the Grateful Dead scene before eventually becoming a worldwide phenomenon.

In the parking lots outside of Dead shows, there was always an area called Shakedown Street (after their song) where fans sold various munchies, merchandise and, of course, drugs. It was at these outdoor hippie bazaars during the late 1980s and ’90s that glassblowing pioneer Bob Snodgrass rose to prominence, crafting pipes in the shape of the Dead’s iconic image of a skull wearing a top hat, which sparked the industry of glass pipes and bongs that followed.

It was also on Shakedown Street outside the Deer Creek Amphitheater in Indiana where, in June 1991, a Deadhead named Greg copped an ounce of herb called “Dogbud” that tasted a bit “chemmy.” That bag contained thirteen seeds, which Greg later grew out to create the now legendary cultivar Chemdog, whose crosses went on to beget Sour Diesel and OG Kush, two of the most popular strains in history.

In fact, when members of the Dead and their families decided to launch their own Cannabis brands — Mickey Hart’s Mind Your Head in 2019 and Garcia’s Hand Picked in 2020 — both included Chemdog among their offerings.

Fare thee well

Regrettably, in addition to weed and psychedelics, Garcia also started using heroin sometime in the mid-1970s. Tragically, his drug use finally caught up with him on August 9, 1995, when he died from a heart attack at the age of 53. Without their beloved founding frontman, the Grateful Dead announced that December that they were disbanding. This past October, bassist Phil Lesh also passed away.

Despite these losses, the band’s surviving members have continued to perform their music in various incarnations, including The Other Ones, Dead and Company, Further and The Dead, among others. But long after the last of the Dead are gone, there will still be millions of stoners and psychonauts who remain forever grateful for their incomparable contributions to our culture.