Over the past century, science has made enormous strides in identifying and understanding the hundreds of chemical compounds in the Cannabis plant and how they affect our physiology. And no man has done more to advance that noble cause than the internationally recognized “Father of Cannabis Research,” Israeli organic chemist Dr. Raphael Mechoulam.

Early Research

During the birth of modern medicine in the 19th century, scientific study of the chemical composition of Cannabis began to take off.

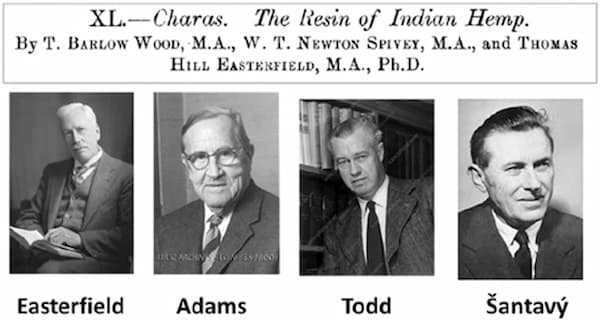

In the 1840s, researchers like French pharmacist (and Club de Hashischin affiliate) Edmond DeCourtive began making Cannabis extracts using ethanol – a concentrate he dubbed cannabin. From these kinds of extracts, chemists began identifying the molecules that would later come to be known as cannabinoids. In 1895, researchers Thomas Wood, W.T. Spivey, and Thomas Easterfield discovered and isolated the first cannabinoid, cannabinol (CBN) – publishing a paper about it in the Journal of Chemical Society in 1899 (though its chemical structure wasn’t fully identified until the 1930s, by British chemist Robert S. Cahn).

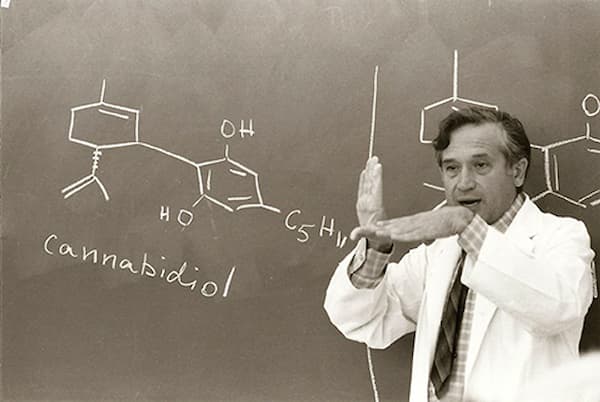

Unfortunately, the enactment of America’s Marihuana Tax Act of 1937 stymied Cannabis research for decades, with one notable exception: A Harvard-trained chemist named Roger Adams, who, in 1939, was actually tasked by the newly-formed Bureau of Narcotics with exploring the plant’s composition. In 1940, using the wild Minnesota hemp supplied by the Bureau, he became the first person to identify, isolate and synthesize cannabidiol, or CBD. Adams – who published 27 studies on Cannabis in the American Journal of Chemistry throughout the 1940s – also synthesized CBN and even identified tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), though he lacked the technology or technique to isolate it. It would be 20 years before another scientist would grab Adams’ academic baton and run with it: That scientist was Dr. Raphael Mechoulam.

From Refugee to Researcher

Raphael Mechoulam was born in 1930 in Sofia, Bulgaria, where his physician father was the head of the Jewish hospital. At the start of World War II, his family was forced to flee and move from village to village to escape the Nazis (his father later spent time in a concentration camp but survived) until emigrating to Israel in 1949. A student of organic chemistry, Mechoulam got his first experience with scientific research while studying insecticides during his stint in the Israeli Defense Forces.

After his service, Mechoulam earned a Master of Science in biochemistry from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem (1952), followed by a Ph.D. from the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot (near Tel Aviv), and postdoctoral studies at the Rockefeller Institute in New York before returning to Israel to begin what would become his life’s work: the exploration of Cannabis chemistry.

Cannabis Curiosity

Why Cannabis? According to Mechoulam, it was simply the lack of existing information on the topic that drew him to it. As he explained in a 2016 interview with Vice:

“I realized the scarce chemical knowledge about the compounds in Cannabis. I found it very surprising: While morphine had been isolated from opium and cocaine from the coca leaf, no one had studied the chemistry of the marijuana plant. It was very odd.”

Due to prohibition, academics couldn’t get research grants involving Cannabis and even feared prosecution for studying it. Luckily, that didn’t deter Mechoulam – despite the fact that Cannabis was illegal in Israel, he came up with an idea on how to get some. In 1962, he asked the director at the Weizmann Institute – where he was working as a junior faculty member – if he knew of any police who could supply hashish for research. As it turned out, the head of investigations at the national police happened to be one of the director’s old army buddies … and after vouching for the young scientist, the officer agreed.

Mechoulam hopped on a bus to a police station in Tel Aviv, where he was given five kilos of Moroccan hashish that had been intercepted while being smuggled in from Lebanon. He thanked the officers, put the hash in his bag, and got back on the bus. Of course, his parcel made for an interesting bus ride home, as he amusedly recalls in the award-winning 2015 documentary about him “The Scientist,” saying, “People on the bus after 15, 20 minutes started asking, ‘What the hell is this very unusual smell?’”

Soon after, Mechoulam and the police learned that any requests for illegal substances required a permit from the Ministry of Health and that their transaction could actually land them all in prison. Nevertheless, after apologies were made, the matter was forgiven and Mechoulam continued to obtain hashish from the police (with a permit) for decades thereafter.

CBD, THC & the NIH

After procuring the hash, the next step was to secure some funding. Mechoulam applied for a research grant from the National Institutes of Health in America but was rejected.

“They told me, ‘It’s not relevant. Nobody smokes marijuana in the U.S. – people do it in Mexico,’” he recalls.

Nevertheless, Mechoulam and his colleagues (Dr. Yehiel Gaoni and Dr. Haviv Edery) began their in-depth study of the hash’s various compounds and cannabinoids (a term which Mechoulam coined). First, in 1963, they isolated CBD and mapped its molecular structure. Then, the following year, using a nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer, they were able for the first time to isolate and map the structure of delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, better known as THC – which, as their experimentation on monkeys soon revealed, was the only compound that produced a psychoactive effect.

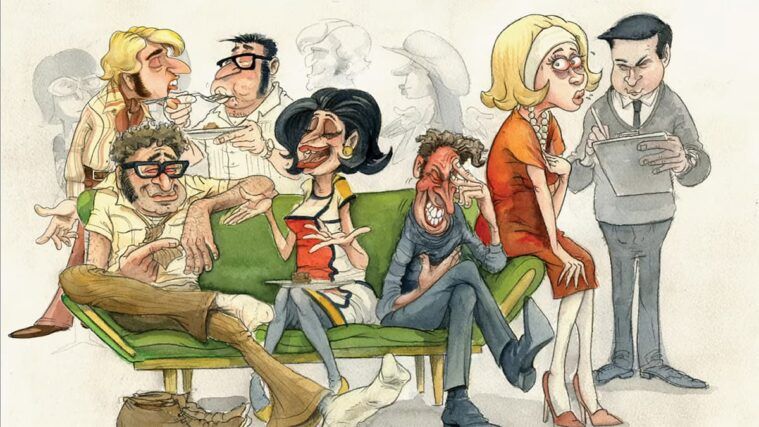

To be sure, though, they’d need to test it on humans. So Mechoulam took a bunch of pure THC powder home and invited a group of friends over for cake – dosing some of the slices with 10mg of THC. While the effects on each individual differed, there was little doubt that they’d identified the correct compound.

On April 1, 1964, they revealed their findings in a paper entitled “Isolation, Structure, and Partial Synthesis of an Active Constituent of Hashish,” published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society. After that, the NIH was suddenly very interested in their “irrelevant” research – sending representatives to Israel to meet with them, observe their work, and take 10 grams of pure THC back to the U.S. with them (which fueled most of the organization’s early research).

Endocannabinoids & the Entourage Effect

In the following decades, Mechoulam and his team at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem continued to make groundbreaking discoveries about Cannabis – identifying and synthesizing over 100 compounds, including cannabinoids like cannabigerol (CBG) and cannabichromene (CBC), as well as Delta 8 and 10 THC.

In the early 1980s, they conducted the first experiments with CBD oil for epilepsy. In the mid-‘80s, their research led to the discovery of two cannabinoid receptors in the human body (dubbed CB1 and CB2) by neuroscientist Dr. Allyn Howlett … which, in turn, led to their discovery of the first endocannabinoid (a cannabinoid-like chemical produced internally by the human body) in December 1992, which they named anandamide (aka the “bliss molecule”).

These discoveries eventually led to the game-changing realization that those receptors comprised a complex, pervasive, and previously unknown network within human anatomy that Mechoulam’s team aptly named the endocannabinoid system, which is believed to be responsible for maintaining homeostasis (regulating the stability of all the body’s other systems).

“The endocannabinoid system is very important,” Mechoulam told Vice. “Almost all illnesses we have are linked to it in some way or another. And that is very strange. We don’t have many systems which get involved with every illness.”

Mechoulam was also the first to propose the concept of the “entourage effect” in 1998 – the hypothesis that the combination of various cannabinoids and terpenes act synergistically to provide benefits they wouldn’t necessarily offer alone.

Foundation for the Future

Thanks to Mechoulam’s work, Israel has become the global leader in medical Cannabis research. In the early 1990s, their Ministry of Health began offering medical marijuana to patients suffering from certain debilitating ailments. And in 2004, they launched an experimental program to study the effectiveness of Cannabis on veterans suffering from PTSD.

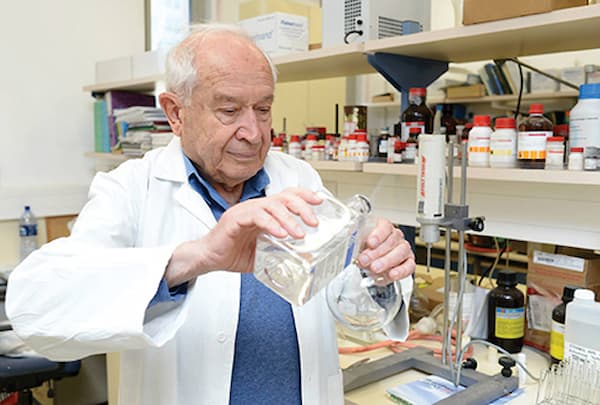

Dr. Mechoulam has now published nearly 400 scientific articles and has been awarded several honorary degrees. He’s a founding member of the International Cannabinoid Research Society and the International Association for Cannabinoid Medicines. He’s been nominated for over 25 academic awards, several of which he won – including two lifetime achievement awards and the esteemed Harvey Prize – widely considered a precursor to the Nobel Prize, for which he’s rumored to be in consideration.

Still, the legacy that the now 92-year-old “father of Cannabis research” seems most concerned with is ensuring that Cannabis is fully accepted and integrated into traditional Western medicine.

“I have spent the better part of my life decoding the mysteries that lie within this incredible plant,” Mechoulam has said. “I believe that cannabinoids represent a medicinal treasure trove which waits to be discovered.”