In the late 19th century, Cannabis was used in countless remedies to treat an array of ailments. Almost immediately after prohibition kicked in in 1937, however, the plant’s medicinal properties were all but forgotten. It would take over half a century before the idea of marijuana as medicine would regain credibility, thanks to the passage of California’s Compassionate Use Act of 1996 – aka Proposition 215. Though many prominent activists were involved in crafting and campaigning for the initiative, there’s one man generally credited as its architect – a gay Vietnam vet turned Cannabis crusader by the name of Dennis Peron.

BIRTH OF AN ACTIVIST

Born on April 8, 1945 in the Bronx, New York, Dennis Robert Peron grew up in a middle-class Italian-American family in a conservative area of Long Island. In 1966, after several unsuccessful attempts to avoid the Vietnam War, he enlisted in the Air Force. But before being shipped off to combat, he spent the Summer of Love in San Francisco, immersing himself in the new counterculture. In 1969, as soon as his tour was up, Peron headed back to the Bay (with two pounds of weed in his duffle bag), where he settled in the Castro District and began his 40-year career as an activist – becoming a Yippie, organizing smoke-ins, and selling weed.

MILK & THE SUPERMARKETS

Throughout the 1970s, Peron operated a series of clandestine Cannabis ‘supermarkets’ around the Castro. First, in 1972, came The Big Top – a ganja grocery store he ran out of the living room of his third-floor walkup at 715 Castro Street. Two years later, he bought a cafe at 16th and Sanchez, turning it into a 420-friendly health food restaurant called The Island (named after the utopian last novel by Aldous Huxley), and converted the apartment upstairs into a pot market. The Island quickly became a hub for the counterculture community – offering both gay rights and marijuana reform activists a safe place to gather, converse and organize. It was there at The Island that Peron developed a deep bond with up-and-coming gay rights advocate Harvey Milk — so much so that he allowed Milk to use The Island as his headquarters for several political campaigns, including his historic election to San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors in 1977.

BIG TOP BUST

On July 20 of that same year, the Big Top was raided by the SFPD Narcotics Squad. Peron, mistaking the plain-clothes police storming up the steps for robbers, threw a five-gallon water jug down the stairs at them – prompting one of the officers to shoot him in the leg, shattering his femur. They arrested Peron (and a dozen or so others) and seized around 200 pounds of weed and some live plants, as well as a stash of other drugs (hash, shrooms, acid and peyote) and nearly a quarter million dollars in cash.

During the trial that followed, the testimony of the lead officer ended up being thrown out after he admitted in front of witnesses that he wished the bullet had hit Peron’s heart so there would be “one less faggot in San Francisco” – an outburst that resulted in a lighter sentence for Peron, who ended up cutting a deal and serving six months in San Bruno County Jail.

Sadly, he was still behind bars when he learned of the tragic assassinations of Milk and Mayor George Moscone. Milk had helped Peron pass Proposition W – a citywide decriminalization measure (which Mayor Moscone backed) that directed the district attorney and law enforcement to stop arresting and prosecuting people for growing, possessing or transferring Cannabis. Though the measure had passed with 56% of the vote, the new incoming mayor, Dianne Feinstein, chose to disregard it.

DEATH & DETERMINATION

When the AIDS epidemic broke out in the 1980s, Castro – being one of the most prominent gay neighborhoods in the nation – was among the most brutally hit. For those dealing with the horrible disease, Cannabis was one of the few things that brought them some relief from their pain and stimulated their appetites to combat the accompanying wasting syndrome. Seeing the suffering all around him only strengthened Peron’s resolve to provide medicinal marijuana to those affected – including his partner, Jonathan West, whose health was rapidly deteriorating.

Despite his weakened condition, though, police showed no compassion when, in January 1990, they again raided the couple’s apartment and allegedly forced West to the ground and beat him with a gun. They then confiscated his weed and arrested Peron on charges of possession and distribution. At the trial that August, an extremely feeble West testified that the marijuana belonged to him and that Peron was merely his caretaker. The judge threw out the charges and told the officers that he “never wanted to see another case like this in court.”

West died two weeks later. He was just 29 years old. He’d stayed alive just long enough to exonerate his love.

Following Johnathan’s death, Peron rededicated himself to reforming California’s Cannabis laws – launching Proposition P (the nation’s first-ever medical marijuana initiative) and “almost single-handedly” collecting the signatures necessary to get it on the ballot. Prop P would decriminalize Cannabis’ medicinal use in San Francisco and allow doctors to recommend it to patients. In November 1991, it passed with an impressive 79% of the vote – illustrating the city’s overwhelming support for medical marijuana and inspiring Peron to open his most ambitious pot shop yet.

THE CANNABIS BUYERS CLUB

The San Francisco Cannabis Buyers Club was founded in 1992 by Peron, with some help from his future husband John Entwistle, longtime activist Mary Jane Rathbun aka “Brownie Mary” (see our Dec 2022 column “Baking a Difference”), and Dr. Tod Mikuriya – a prominent psychiatrist/medical doctor and Cannabis advocate who served as the club’s medical coordinator.

Considered the first true medical marijuana dispensary in the country, the five-story dispensary at 194 Church Street was described as a cross between a community center and an Amsterdam coffeeshop. The club offered a variety of edibles and strains to its patients, as well as starter plants and various paraphernalia. At its height in 1996, the CBC reportedly boasted nearly 12,000 members and over 100 employees – most of whom were patients themselves.

Emboldened by the success of Prop P and the CBC, Peron and his allies began working on what would become their most significant achievement: Proposition 215.

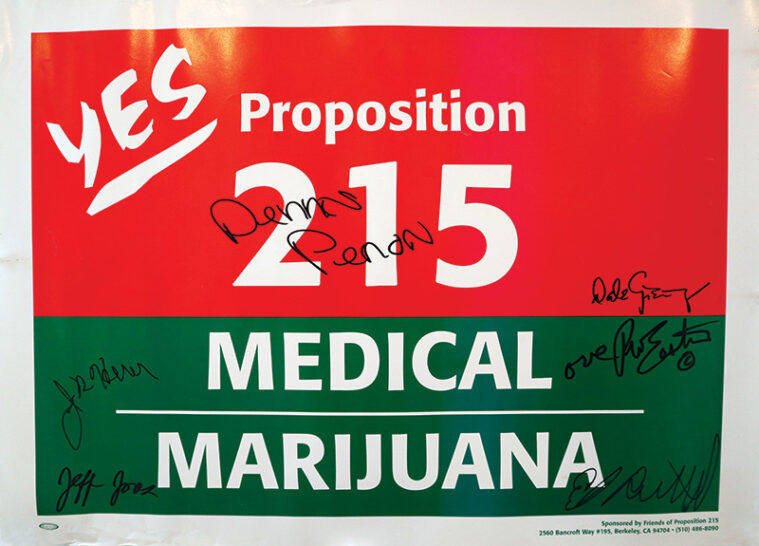

PROPOSITION 215

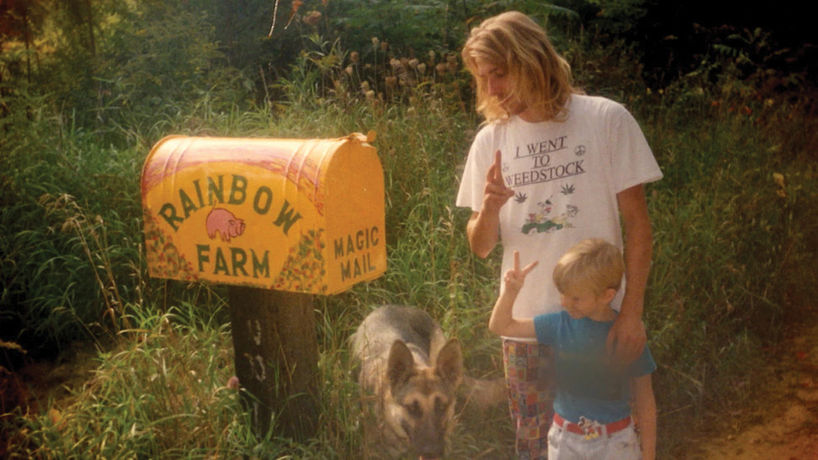

Since the passage of Prop P, the state legislature had approved several medical marijuana bills – but they were all vetoed by Governor Pete Wilson. Frustrated with the lack of progress, Peron once again appealed directly to the voters. In 1995, he partnered with California NORML Director Dale Gieringer and Los Angeles Cannabis Resource Center’s Scott Tracy Imler to create Californians for Compassionate Use – a political action committee devoted to getting medical marijuana on a statewide ballot.

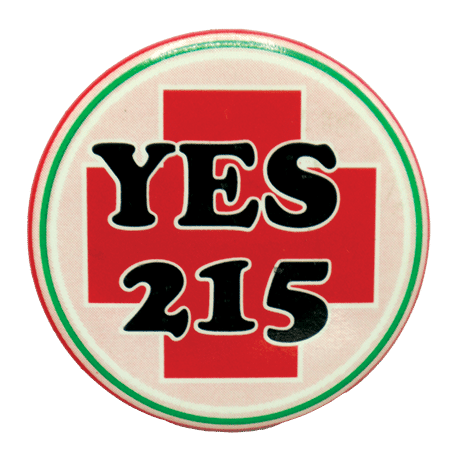

In a series of meetings at the CBC, Peron and his allies sat down and hashed out the details of a new statewide medical marijuana initiative they called The Compassionate Use Act, aka Proposition 215. Essentially, Prop 215 was an amendment to the California Health and Safety Code that exempted physicians who recommend Cannabis – as well as patients and designated caregivers who cultivate and possess Cannabis for medical use – from criminal prosecution.

With the help of Drug Policy Alliance founder Ethan Nadelmann and political consultant Bill Zimmerman, the group raised close to $2 million from sympathetic entrepreneurs and philanthropists such as liberal billionaire George Soros, Progressive Insurance owner Peter Lewis, and Men’s Wearhouse founder George Zimmer. After completing the bill in the fall of 1995, they had just six months to collect the 500,000 signatures necessary to get it on the ballot for November 1996 – which they did, with the help of their donors and a small army of activist volunteers.

TRIBULATION & TRIUMPH

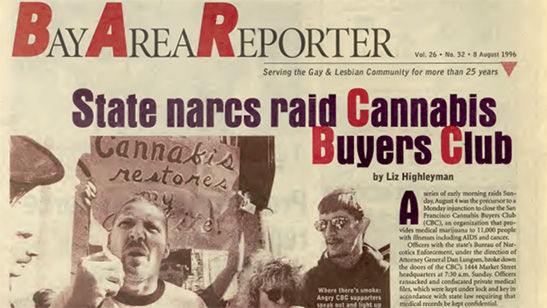

Predictably, the measure faced heavy opposition from law enforcement and elected officials – including California’s governor and senators, as well as former presidents Ford, Carter, and Bush, who all issued statements condemning the bill. California’s Attorney General Dan Lungren, however, went a lot further: On August 4, 1996, he directed the California Bureau of Narcotics Enforcement to raid and shut down the CBC – alleging that the club was selling marijuana to minors and people without legitimate medical need. They reportedly seized 150 pounds of Cannabis, 400 plants, $750,000 in cash, and thousands of patients’ doctor recommendation letters.

Then, on October 5, Lungren had Peron arrested and charged with possession and criminal conspiracy to distribute marijuana across the Bay in Alameda County – a jurisdiction he calculated would be less sympathetic. Ironically, however, instead of discrediting Dennis and Prop 215, it actually garnered sympathy for the cause and drew criticism from many in the public eye – including cartoonist Garry Trudeau, who, in his syndicated “Doonesbury” comic strip, lampooned Lungren for arresting sick people. In the weeks before Election Day, support for the initiative actually increased and a few prominent health care organizations even endorsed it. Prop 215 ended up passing with 56% of the vote, making California the first state in America to legalize medical marijuana – an example that other states would soon follow.

“The passing of 215 lit a fuse around the world,” Peron once said. “It changed everything. They can’t turn back the clock now.”

AFTERMATH & LEGACY

Of course, the fight didn’t end there. On December 30, 1996, Attorney General Janet Reno and Drug Czar Barry McCaffrey held a press conference at Columbia University in which they threatened any doctors who recommended Cannabis with revocation of their DEA registration, without which they wouldn’t be able to prescribe medications. And in fact, many doctors had to fight to keep their licenses after recommending Cannabis to their patients in the years that followed.

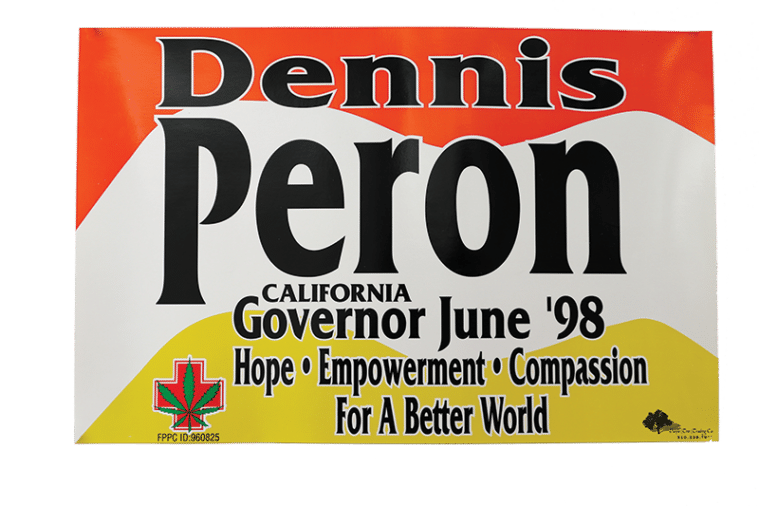

After a drawn-out legal battle with Lungren, the SF Buyers Club was ultimately forced to close its doors on May 26, 1998. That same year, Peron ran (unsuccessfully) against his nemesis in the Republican primary for governor. After that, Peron gave up on operating dispensaries – instead moving to a farm in Lake County to grow Cannabis. He and his husband eventually returned to San Francisco and opened a small Cannabis-friendly bed and breakfast they called the Castro Castle.

A vocal advocate for Cannabis until his death from lung cancer on January 27, 2018, Dennis Peron will forever be remembered as “the father of medical marijuana.”